Charles Spinelli Unlocks the Secrets of Designing a

May 19, 2025What to Expect from a Financial Advisor in

May 17, 2025Steven Rindner On Impact of Weather Conditions in

May 15, 2025Is Post-Op IV Ozone Therapy Useful for Joint

May 03, 2025How Do You Take Care of Your Vehicle

May 03, 2025Does Oxygen Facial Reduce Large Pores Too?

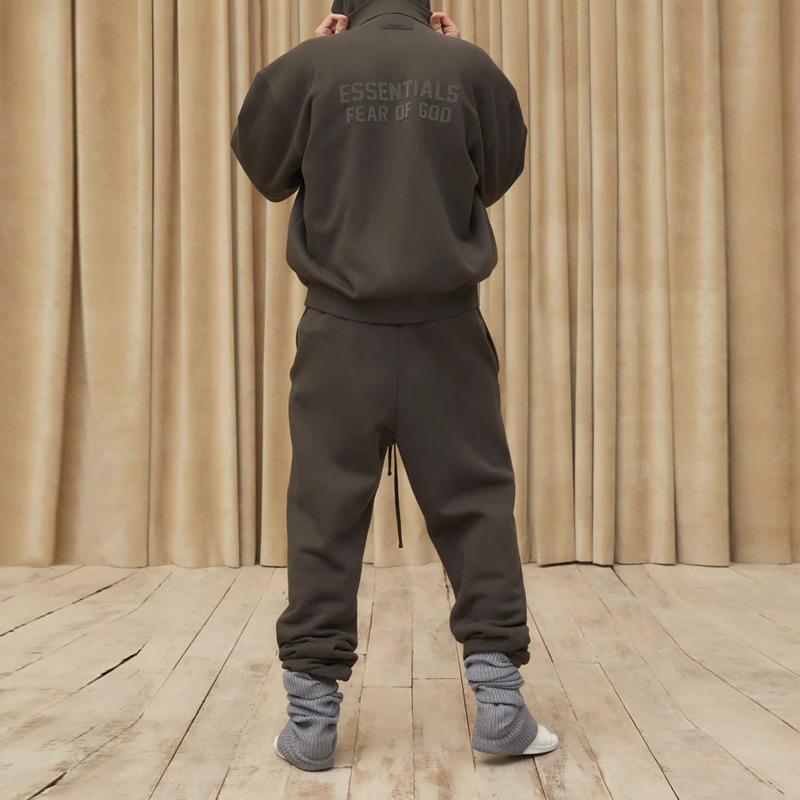

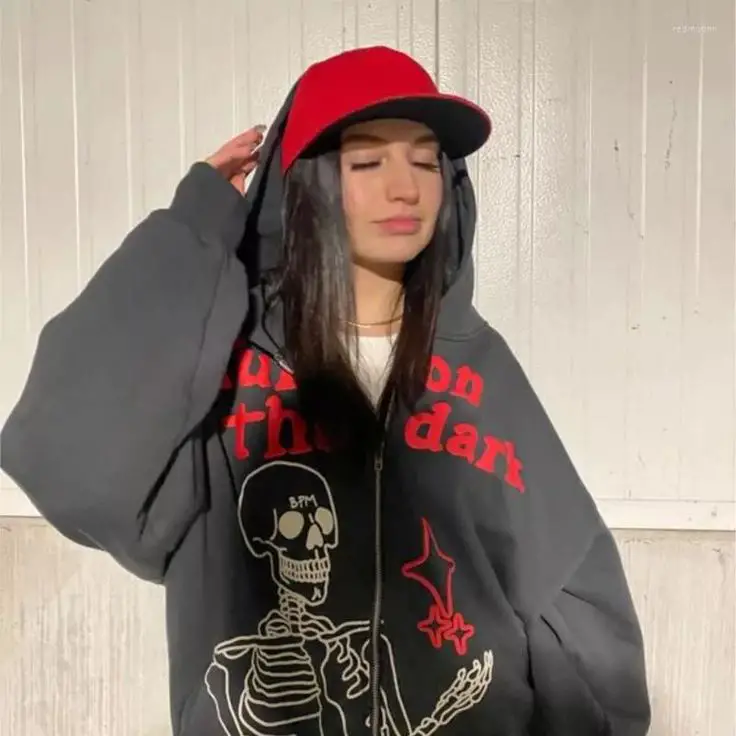

May 03, 2025Discover the Bold Streetwear Power of the Iconic

May 03, 2025Choose VIP Travel Agency for Luxury Adventures

May 02, 2025Why Choose HydraFacial for Flawless Skin in Dubai?

May 02, 2025Bitachon for Beginners: A Quick Guide

May 02, 2025Top Skin Whitening Treatments in Dubai: A Quick

May 02, 2025Download GB WhatsApp APK – Updated Version (2025)

May 02, 2025Top Guma – Affordable Tires for Every Car,

May 02, 2025Top Guma – Wide Selection of Car Tires

May 02, 2025GV GALLERY® || Raspberry Hills Clothing Store ||

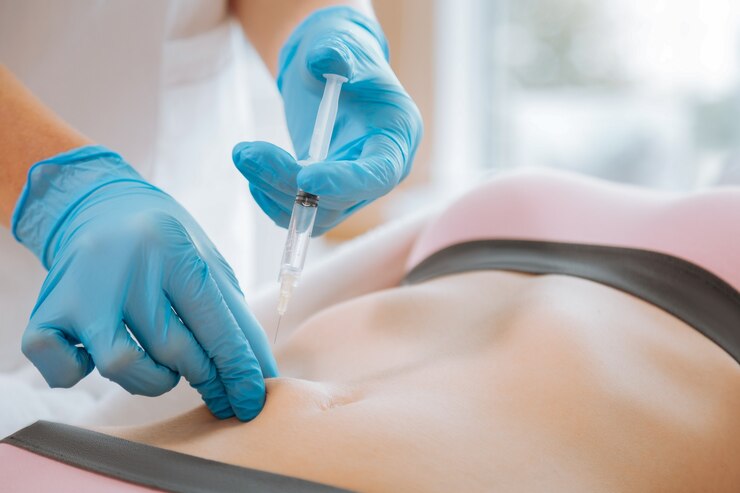

May 02, 2025How Does Wegovy Injections Compare to Saxenda?

May 02, 2025Resume writing services – hirex

May 02, 2025Finding the Best Naperville Fence Company for Your

May 02, 2025Unlock the Power of Numbers with a Numerology

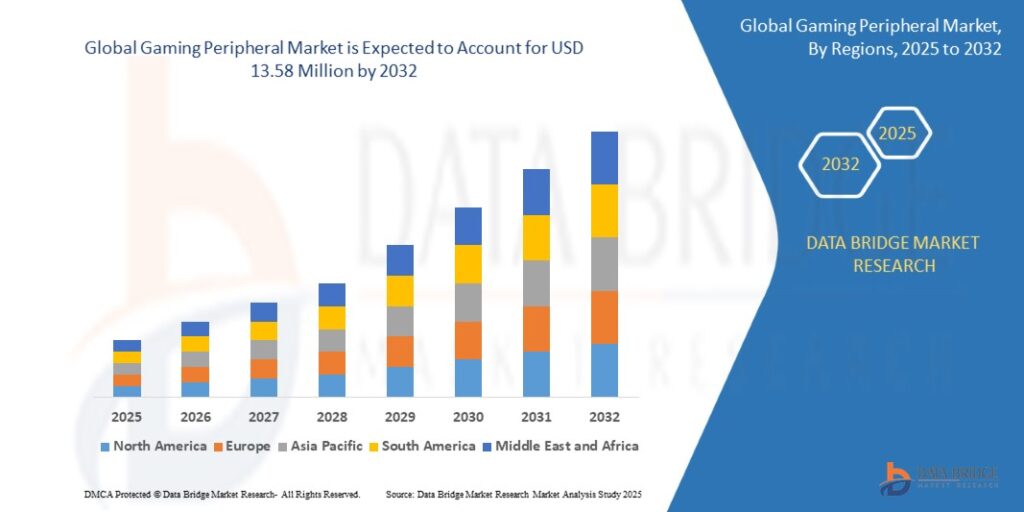

May 02, 2025Title: Top Online Game Genres to Watch in

May 02, 2025Who Is the Biggest Enemy of Lord Vishnu

May 02, 2025Reliable Manchester to Airport Taxi Service – Fixed

May 02, 2025Complete Greenhouse Solutions by EKO TEPLYTSIA Kyiv

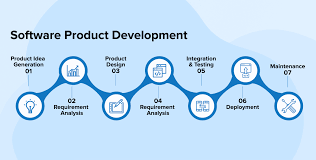

May 02, 2025How Henceforth Leads as a Premier App Development

May 02, 2025High-Quality Jewellery Design CAD Files Online

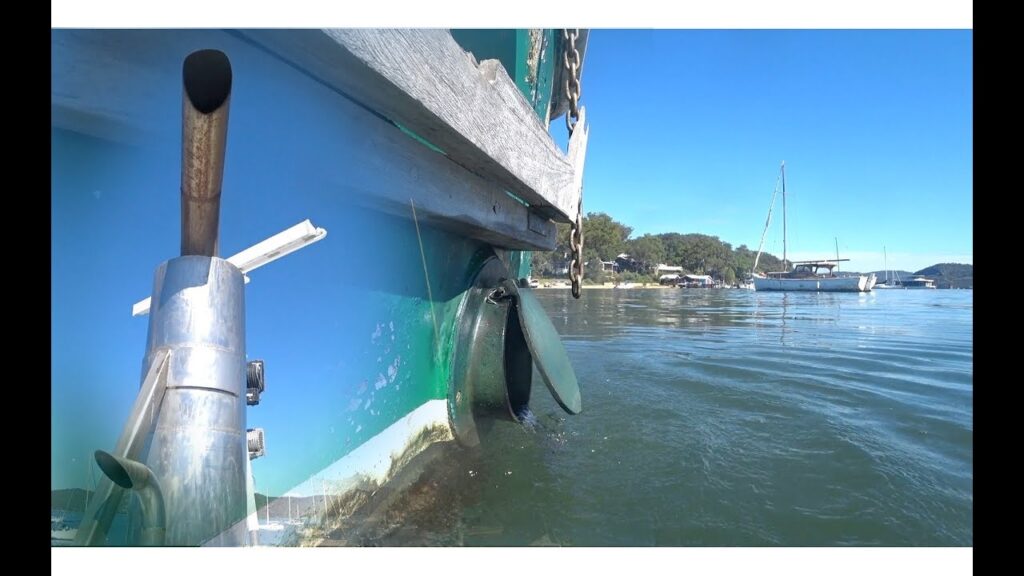

May 02, 2025Tassie-Tough MTA: Where Stability Meets Progress

May 02, 2025The Ultimate Guide to ISO Training: Top Management

May 02, 2025Crafting Cute and Creative Party Decor for Every

May 01, 2025Halal Certification: What It Is and Why It’s

May 01, 2025How Professional CIPD Help Can Boost Your Academic

May 01, 2025Choosing the Right Retirement Homes in Sydney: A

May 01, 2025Drive in Style with Premium Android Car Radios

May 01, 20256+ Years of Quality Android Car Stereo Installations

May 01, 2025Reliable Romiley to Manchester Airport Taxi Service

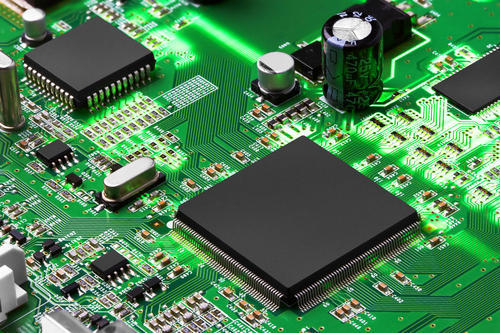

May 01, 2025United States Semiconductor Market Size & Share |

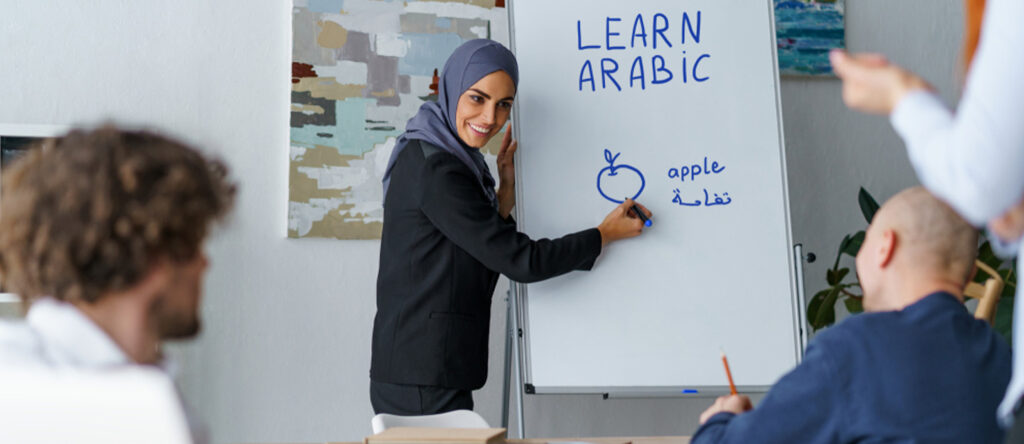

May 01, 2025Masters in Ireland for Indian Students: Best IT

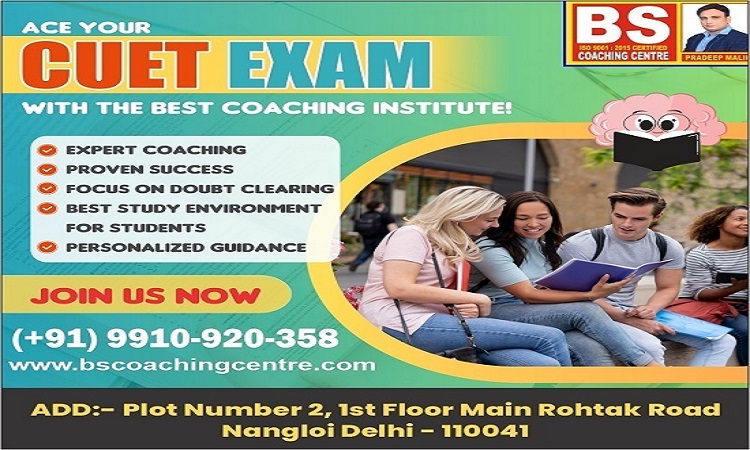

May 01, 2025One Goal. One Result. The Best CUET Coaching

May 01, 2025Top Castles and Palaces to Visit in Hungary

May 01, 2025How to Choose the Best PPC Management Company

May 01, 2025Living Room Design Tips from a Knoxville Remodeling

May 01, 2025Are One-Size-Fits-All Marketing Services Worth It?

May 01, 2025Badson US || Official Badson Clothing Store ||

Apr 30, 2025Bajaj Pulsar NS 160: The Perfect Bike for

Apr 30, 2025محل عطور فاخر يقدم أجود الروائح وتجربة تسوق

Apr 30, 2025The Timeless Allure of Agarwood Oud

Apr 30, 2025Hire Laravel developer at affordable price

Apr 30, 2025Is ClearLift Laser Suitable for Mature Skin?

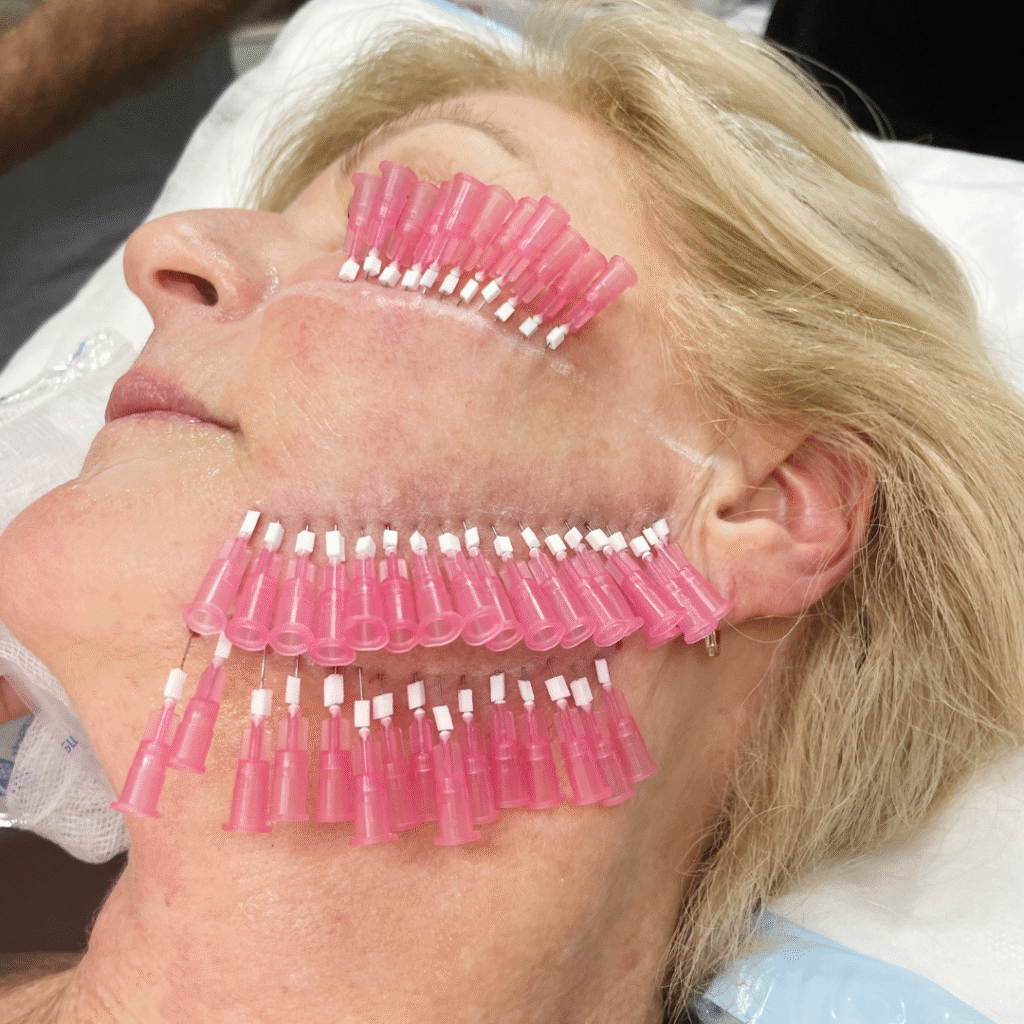

Apr 30, 2025Is PDO Mono Threads Right for Your Skin?

Apr 30, 2025ISO 45001 Training: Essential Steps for a Safer

Apr 30, 2025Trusted Mobile Notary in Pasadena – Fast &

Apr 30, 2025Proven Facts to Fix QuickBooks Error Code 15276

Apr 30, 202510 Compelling Reasons to Buy Space Binoculars

Apr 30, 2025Why Are i7 Laptops Still the Top Pick

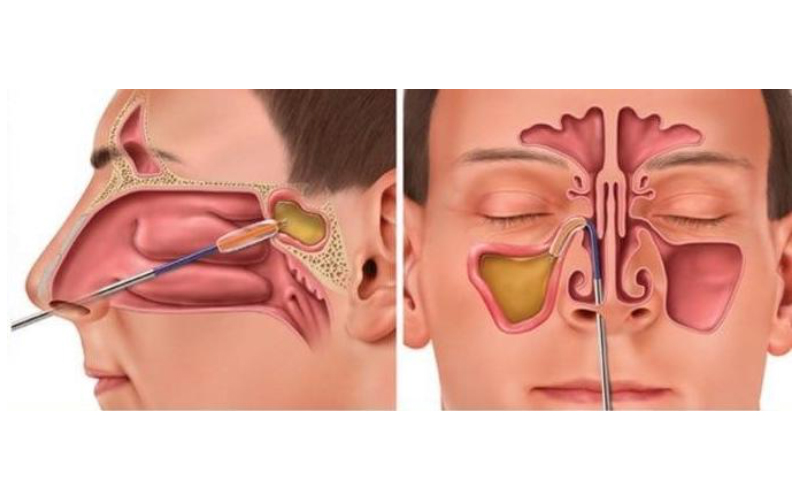

Apr 30, 2025What Is Rhinoplasty and How Does It Work?

Apr 30, 2025Unlocking Pharma Success with Real World Data in

Apr 29, 2025Top SEO Services in Los Angeles: Boost Your

Apr 29, 2025Does ClearLift Laser Work on Acne Scars?

Apr 29, 2025Is Hair Transplant Effective for Balding Men?

Apr 29, 2025Insurance Company in Abu Dhabi – Tailored Solutions

Apr 29, 2025GB WhatsApp APK Download 2025 (Latest Version)

Apr 29, 2025Is Fat Injections Better Than Fillers for Facial

Apr 29, 2025Reliable Taxi from Stockport to Manchester Airport

Apr 29, 2025Luxury Sprinter Van Limo Service – Comfort, Style

Apr 29, 2025Our Uniting Classic USA Craft with Chrome Heart

Apr 29, 2025How a Web Development Company Builds Websites That

Apr 29, 2025How a Moisture Analyzer Improves Product Quality

Apr 29, 2025Reporting CSRD : Automatisez vos processus

Apr 29, 2025Top 10 Features to Look for in a

Apr 29, 2025Top Platforms to Sell Google Play Gift Card

Apr 29, 2025Dust Collector Manufacturer in India

Apr 29, 2025Pharmacovigilance in New Zealand – DDReg Pharma

Apr 29, 2025The #1 Natural Snoring Solution — NiteHush Pro

Apr 29, 2025Understanding Mental Health: A Beginner’s Guide

Apr 29, 2025How to Choose Perfume Based on Personality?

Apr 29, 2025Pharma Commercial Analytics and Consulting in 2025

Apr 29, 2025Best Airport Limo Service – Comfort, Luxury, and

Apr 29, 2025Fast Car Battery Replacement in Abu Dhabi –

Apr 29, 2025Mobile Tyre Repair in Abu Dhabi: 24/7 Roadside

Apr 29, 2025Complete Guide to Car Towing Services : 24/7

Apr 28, 2025Why Companies Need a Better Strategy for a

Apr 28, 2025Top Features to Look for When Developing Book

Apr 28, 2025Southampton Limo Service | Luxury Car & Airport

Apr 28, 2025Black Leather Coat for Women for Effortless Winter

Apr 28, 2025Top 7 Secrets to Extend Your Car AC

Apr 28, 2025Taxi from Glasgow to Manchester Airport | Affordable

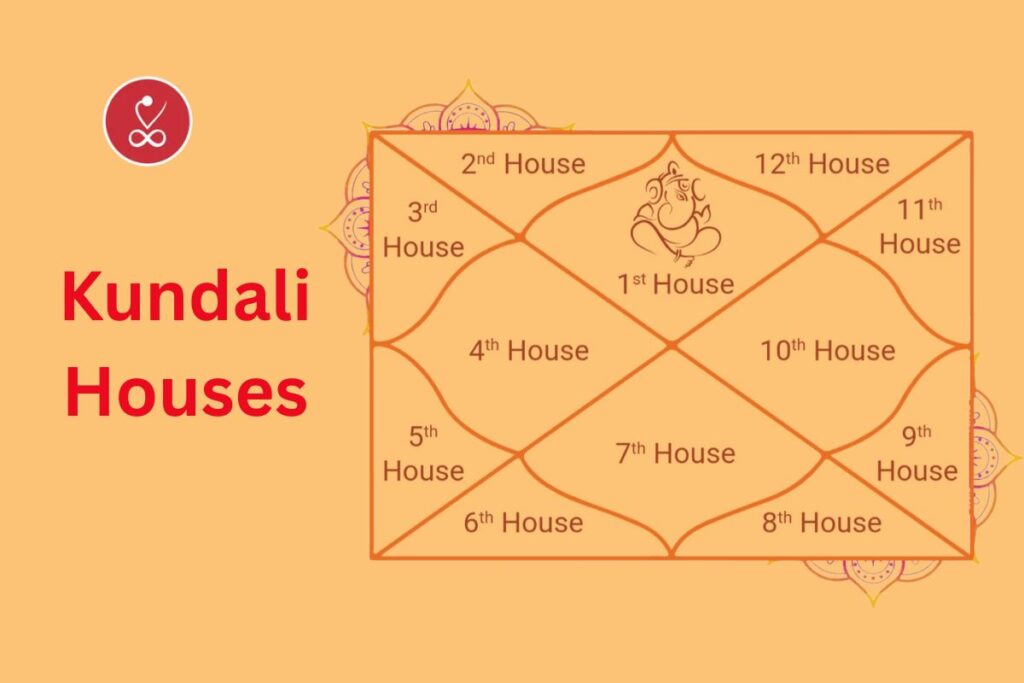

Apr 28, 2025Kundali Houses Explained: Your Horoscope Secrets

Apr 28, 2025Top 10 Business Schools in Jaipur You Shouldn’t

Apr 28, 2025Why Invest in Property in Sector 10 &

Apr 28, 2025How to Choose the Right Solar Battery for

Apr 28, 2025Is Freckles and Blemishes Treatment Permanent?

Apr 28, 2025Unique Themes for Adelaide Wedding Receptions

Apr 28, 2025How to Grow Your Instagram Followers: A Strategic

Apr 28, 2025Book Trusted Newark Airport Limo Services | Noor

Apr 27, 2025GB WhatsApp APK (2025) – Latest Version Download

Apr 27, 2025Badson US || Official Badson Clothing Store ||

Apr 27, 2025Why Corteiz Hoodie is Perfect for Everyone

Apr 26, 2025Does Orlebar Brown Clothing Provide Fabric of the

Apr 26, 2025The Loverboy Hat: A Revolutionary Symbol in the

Apr 26, 2025In Glock We Trust Shirt has the most

Apr 26, 2025Why Sp5der Hoodie Is The Best Accessory You

Apr 26, 2025The Emergence of Hellstar Clothing in the Fashion

Apr 26, 2025Serenede jeans– Top Quality Brand

Apr 26, 2025Everything You Need to Know About Swiss Oud

Apr 26, 2025Top 8 Hayati Pro Max 6000 Flavours that

Apr 26, 2025Everything You Need to Know About Premium Oud

Apr 26, 2025Les meilleures saveurs de vapotage de Ghost Pro

Apr 26, 2025Complete Information on Original Oud Attar and Its

Apr 26, 2025De beste vaping smaken van Ghost Pro 3500

Apr 26, 2025Everything You Need to Know About White Oud

Apr 26, 2025Everything You Need to Know About Deer Musk,

Apr 26, 2025Everything You Need to Know About Oud Hindi:

Apr 26, 2025Unlock Your Week: Aquarius Weekly Horoscope Guide

Apr 26, 2025Does Acne Scar Treatment Lighten Dark Marks?

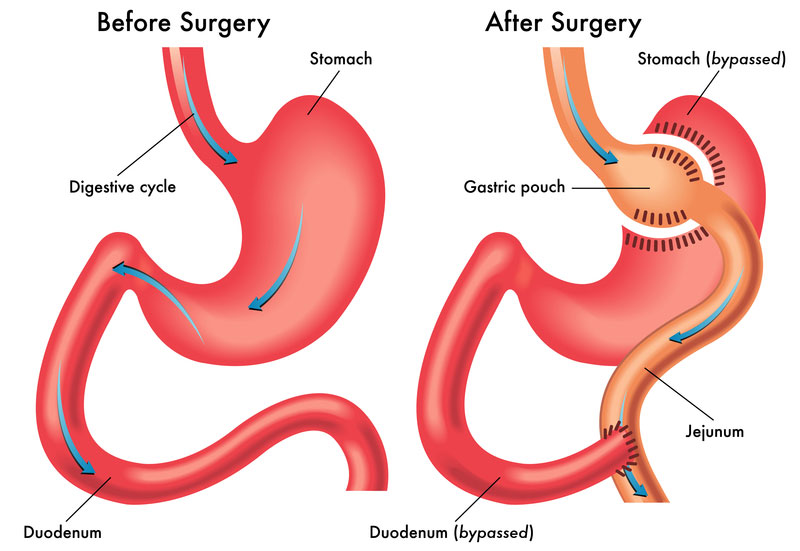

Apr 26, 2025Affordable Gastric Bypass Surgery for Weight Loss in

Apr 25, 2025The Pros and Cons of Static Site Generators

Apr 25, 2025Affordable Men’s Fashion: Best Stores to Shop

Apr 25, 2025Boost Your BPO Performance with Smart CRM Software

Apr 25, 2025How to Raise Emotionally Strong Kids as a

Apr 25, 2025Gallery Dept T-Shirt: Streetwear

Apr 25, 2025How to Make Your Hair Look Shiny and

Apr 25, 2025Is Your Hampshire Website Mobile-Friendly?

Apr 25, 2025Top 10 Electrical Companies in Dubai

Apr 25, 2025Unlock the Web with CroxyProxy – The Ultimate

Apr 25, 2025What are the common mistakes that you have

Apr 25, 2025How to Maintain Non-Surgical Hair Replacement?

Apr 25, 2025The Benefits of Hiring a Local Canberra Wedding

Apr 25, 2025Need a Blocked Sink Fix in Stourbridge? Contact

Apr 25, 2025Boost Your Business with Local SEO Services in

Apr 24, 2025San Diego SEO Services for Higher Rankings &

Apr 24, 2025Real Estate App Development: Essential to Build a

Apr 24, 2025Empyre | Empyre Jeans & Pants | Official

Apr 24, 2025The Rise of Natural Skin Care: Is Makeup

Apr 24, 2025Level Up Your Irrigation Game with These Top-Rated

Apr 24, 2025Soil Pipe Blocked Again? Here’s How to Solve

Apr 24, 2025Struggles Faced by New Moms & Tips to

Apr 24, 2025The Best Passive Real Estate Investment Options in

Apr 24, 2025The Pros and Cons of Investing in Custom

Apr 24, 2025Website Design Pitfalls for Small Businesses: How to

Apr 24, 2025The Role of SEO Tools in a Data-Driven

Apr 24, 2025Choosing the Right Electrician in Adelaide

Apr 24, 2025How Retargeting Can Drive Conversions and Boost ROI

Apr 24, 2025How to Choose the Right Disability Support Provider

Apr 24, 2025Private Taxi from London to Manchester Airport –

Apr 24, 2025How Technology is Changing the Path of Marriage

Apr 24, 2025Mukhyamantri Kisan Kalyan Yojana

Apr 24, 2025Is Organic Pumpkin Peel Better Than Chemical Peels?

Apr 24, 2025Building Smart Chatbots with PHP for Better UX

Apr 24, 2025Professional Help With Writing Thesis for Students

Apr 24, 2025The Kashyap Samhita and the Role of CSS

Apr 24, 2025NYC Cleaning & Maintenance – Trusted Experts for

Apr 23, 2025The Ultimate Guide to : A Luxurious Travel

Apr 23, 2025Realme 2025 Vision: AI Smartphones, & What’s Next

Apr 23, 2025How to Save Money on Car AC Repairs:

Apr 23, 2025Elevating Hygiene Standards in Every Space

Apr 23, 2025Top Certifications Pursue Alongside Your MS in Data

Apr 23, 2025Why Gold Bracelets Are a Must-Have in Every

Apr 23, 2025Smart Property Management Across the New York Metro

Apr 23, 2025Everything You Need to Know About Tummy Tuck

Apr 23, 2025Leo Daily Horoscope – Your Complete Guide

Apr 23, 2025Why Sure Shade Is the Leading External Venetian

Apr 23, 2025The Truth About Finding a Limo Service That’s

Apr 23, 2025Top Benefits of Virtual Office Valdosta GA for

Apr 23, 2025Your Guide to Luxury and Reliability in Northern

Apr 23, 2025UnitConnect: Simplify Commercial Property Management

Apr 23, 2025Smarter Real Estate Tools with UnitConnect Software

Apr 23, 2025How to Safely Overclock with the Intel Overclocking

Apr 23, 2025What Interest Rate Hikes Really Mean for Stock

Apr 23, 2025The Powerful Ruby: Discover the Top Ruby Gemstone

Apr 23, 2025Affordable Taxi from London to Manchester Airport

Apr 23, 2025Unlocking the Secrets of the Triangle in Palmistry

Apr 23, 2025Best IT Services in Oakland for Startups &

Apr 23, 2025How do I speak to someone at Breeze?

Apr 23, 2025How do I talk to a real person

Apr 23, 2025Buy Get Well Soon Flower Online for Her

Apr 23, 2025California Needs Drivers: Apply Now for the Best

Apr 23, 2025Botox Isn’t Just for Women: Men Embrace a

Apr 23, 2025Master Tableau with Expert Tableau Assignment Help

Apr 23, 2025The Rise of Cortiez Cargos: A Streetwear Staple

Apr 23, 2025Essentials Shorts: The Perfect Blend of Comfort and

Apr 22, 2025Why Choosing a Content Writing Agency in Houston:

Apr 22, 2025How to Use Your Intuition to Create Magnetic

Apr 22, 2025Mastering Evidence-Based Practice in NURS-FPX 4030

Apr 22, 2025Is Male Hair Loss Fixed by Best Trichologists?

Apr 22, 2025Food Safety Leader: FSSC 22000 Lead Auditor Course

Apr 22, 2025Top 10 Things to Know Before Visiting Maine

Apr 22, 2025Top Benefits of Installing Sliding Glass Doors in

Apr 22, 2025Book Trailer Services: A Smart Way to Promote

Apr 22, 2025Everything You Need to Know About Buying a

Apr 22, 2025Trusted Experts for Quality Cleveland Roof Repairs

Apr 22, 2025ISO 9001 Lead Auditor Training in Bangalore

Apr 22, 2025Broken Promises and the Healing Power of God

Apr 22, 2025How to Choose the Best Body Spa in

Apr 22, 2025Originalteile und Nachbauteile bei ORAP GMBH

Apr 22, 2025Original- und Nachbauteile direkt vom Fachhändler

Apr 22, 2025Ihr Partner für hochwertige Autoteile im Groß- und

Apr 22, 2025Get Your Towbar Fitted by Experts in Bishop’s

Apr 22, 2025How Body Pillow Shapes Affect Your Spine, Joints,

Apr 22, 2025The Role of Solar Power in Sustaining Military

Apr 22, 2025Which Areas in Dubai Have the Most Promising

Apr 22, 2025Why ISO 14001 Lead Auditor Training Could Be

Apr 22, 2025Discover New Builds in Easton: Modern Living

Apr 22, 2025Tips to choose the best kids backpack

Apr 22, 2025How Is G Cell Treatment Different From PRP?

Apr 22, 2025Which Football League Offers the Best Tactical Depth

Apr 22, 2025Is Renting or Buying a Home Better for

Apr 22, 2025A Smarter Way to Trade Stocks, Forex, and

Apr 22, 2025Graceful Church Suits Every Woman Should Own

Apr 22, 2025Recruitment agency in delhi- hirex

Apr 22, 2025Badson US || Official Badson Clothing Store ||

Apr 22, 2025Corteiz Clothing UK RTW Official Store | Cortiez

Apr 21, 2025Explore Livingston Park and Cabin Rentals in Texas

Apr 21, 2025Best Peking Duck and Curry Crab in Houston

Apr 21, 2025Finding the Right Pet Veterinary Clinic in Qatar

Apr 21, 2025Maximize Space and Style with Stackable and Metal

Apr 21, 2025Embrace the East with Every Sushi Roll at

Apr 21, 2025Sushi Point: Discover the True Spirit of Sushi

Apr 21, 2025Authentic Eastern Flavors, Perfected at Sushi Point

Apr 21, 2025How Do i5 and i7 Processors Compare for

Apr 21, 2025Samsung A26 Price in Pakistan – Specs You

Apr 21, 2025Technical SEO Done Right: Tips from a San

Apr 21, 2025Affordable SEO Services: A Comprehensive Guide

Apr 21, 2025Does Fat Injections Help Sculpt the Body?

Apr 21, 2025MBA in HR Management in Jaipur: Classroom to

Apr 21, 2025Everything You Need to Know About Liposuction in

Apr 21, 2025Find out what colleges in Jaipur offer mechanical

Apr 21, 2025Private Taxi from Blackpool to Manchester Airport –

Apr 21, 2025Intel HD Graphics vs. Dedicated GPUs: What’s Better?

Apr 21, 2025StrikeIT: Trusted SEO Company in Lucknow

Apr 21, 2025Why Split & Multi-Split ACs Suit Homes and

Apr 21, 2025Does Botox for Sweaty Gland Block All Sweat?

Apr 21, 2025Best Custom Patches in Malaysia

Apr 21, 20255 Important Health Benefits Of The Shecup Silicone

Apr 21, 2025Part-Time Jobs in Germany for International Students

Apr 21, 2025Affordable Taxi from Blackpool to Manchester Airport

Apr 20, 202570 Inch Bed Frame Maintenance Tips: to Keep

Apr 19, 2025The Beauty of Handmade Shell Jewellery

Apr 19, 2025Exotic Ride Rent A Car in Dubai

Apr 19, 2025WordPress Experts for High-Converting Sites

Apr 19, 2025Key Benefits of Combining Your MOT Test and

Apr 19, 2025Best gold buyers |Sell gold for cash |Hindustan

Apr 19, 2025Statistics Assignment Help – Expert Stats Solutions

Apr 18, 2025Mertra Clothing || Sale Up To 40% Off

Apr 18, 2025Rhinoplasty Cost in Lahore Explained: Find the Right

Apr 18, 2025E-Commerce and Q-Commerce: Compare all Details

Apr 18, 2025Ukraine Premier Vascular Center – Discover AngioLife

Apr 18, 2025Trusted Vascular Solutions in Ukraine

Apr 18, 2025Best Ethernet Cable for Gaming: A Perfect Guide

Apr 18, 2025Sector 140A Noida: A Prime Location for Retail

Apr 18, 2025Unlocking the Power of Ethernet: How It Fuels

Apr 18, 202515 Budget-Friendly Home Remodeling Ideas That Make a

Apr 18, 2025What Should You Know Before Getting Laser Hair

Apr 18, 2025Private Taxi from Birmingham to Manchester Airport

Apr 18, 2025Not Just Pretty – Design a Patio That

Apr 18, 2025Understanding Your CIBIL Score and Its Importance

Apr 18, 2025How Well Does the Intel Arc GPU Perform

Apr 18, 2025Vicdigit Technologies

Apr 18, 2025The Ultimate Guide to Corrugated Boxes

Apr 18, 2025Best Ethernet Cable for Gaming: A Perfect Guide

Apr 17, 2025High-Quality Seat Covers and Mats for Your Car

Apr 17, 2025How to Prepare for Freckles and Blemishes Treatment?

Apr 17, 2025The Top Reasons to Choose Lake Tahoe Boat

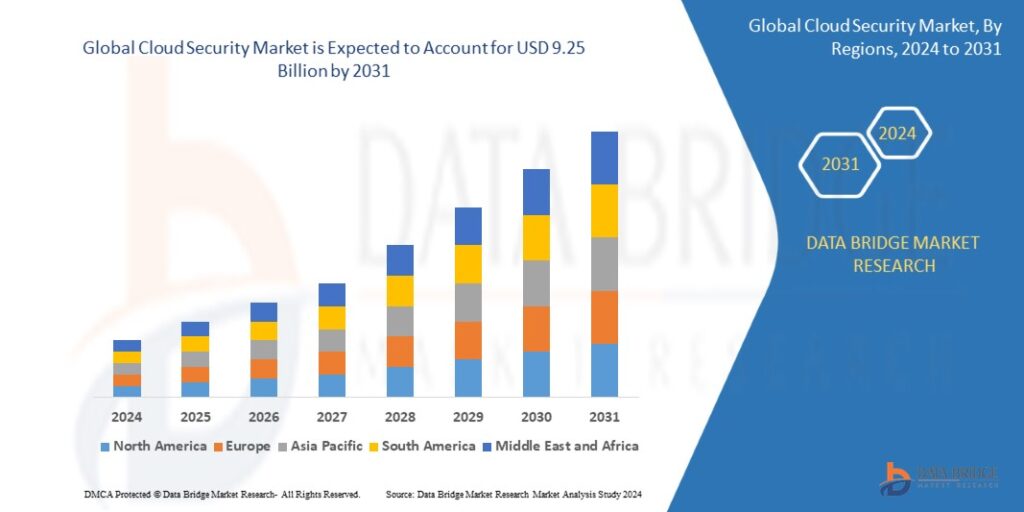

Apr 17, 20252031 Industry Report: Key Drivers Fueling the Data

Apr 17, 20259 Scenes Where i7 Laptops Are the Better

Apr 17, 2025Smart Features of Tapmoon Token That You Need

Apr 17, 2025Process Mining Software Market Size to Skyrocket by

Apr 17, 2025Explore a Wide Selection of Smoking Essentials at

Apr 17, 2025Section 125 Tax Savings Plans: What Every Company

Apr 17, 2025Targeted Musculoskeletal Treatment in Edinburgh

Apr 17, 2025How to Layer Skincare with Acne Scar Treatment?

Apr 17, 2025Pizza Novato Is a Must-Try Culinary Experience

Apr 17, 2025How Cloud Solutions in Dubai Are Enabling Remote

Apr 17, 2025How to Get Ready for Your Anti-Aging Facelift

Apr 17, 2025Reliable Solar Panels and Systems for Your Home

Apr 17, 2025Should You Fight for More Disability Benefits and

Apr 17, 2025Modular Office Workstations To Boost Productivity

Apr 17, 2025Find Your Ideal Tech Candidate with EvoTalents

Apr 16, 2025How to Buy a Business in Florida: A

Apr 16, 2025Empowering the Next Generation of Leaders at Lviv

Apr 16, 2025A Vision for the Future of Ukrainian Education

Apr 16, 2025AWS vs. Azure vs. Google Cloud for Hosting

Apr 16, 2025How IV Ozone Helps You Recover Faster from

Apr 16, 2025Why Laundry Services Are Smart for Your Busy

Apr 16, 2025How Hiring an SEO Expert Pays Off for

Apr 16, 2025Decorative LED Lighting for Garden, Backyard & Home

Apr 16, 2025Create Atmosphere with LED Trees & Solar Lights

Apr 16, 2025Comprehensive SEO Services in Dubai: From On-Page to

Apr 16, 2025The Future of Web Design and What It

Apr 16, 2025Transform Your Journey with DNA-Guided Weight Loss

Apr 16, 2025Embrace Wellness at Your Doorstep: The Rise of

Apr 16, 2025Silver Wound Dressing Market Outlook 2031

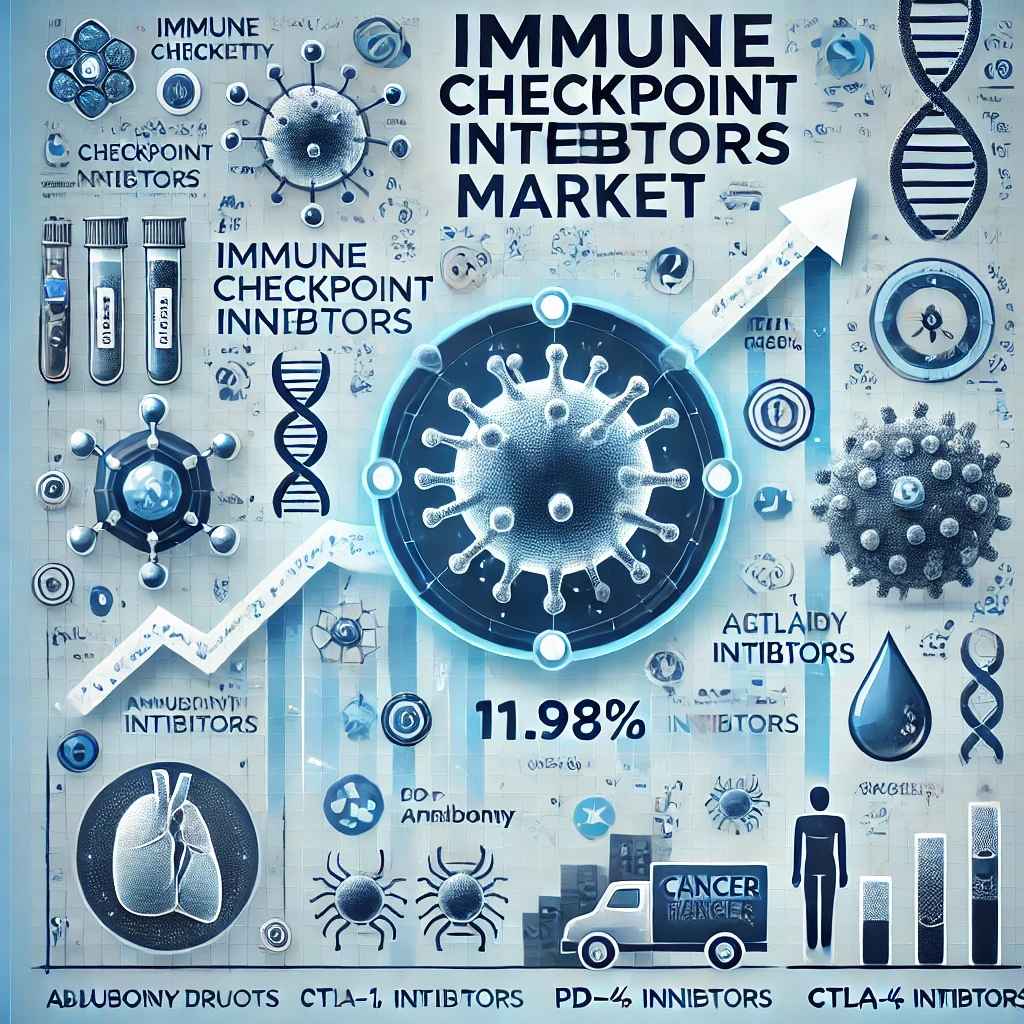

Apr 16, 2025Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors Market Analysis 2033

Apr 16, 2025Chronic Disease Management Market Disruption

Apr 16, 2025Medical Gas Equipment Market Strategy Guide

Apr 16, 2025How FSM Software Enhances Technician Productivity

Apr 16, 2025Top 5 Online BIM Courses in 2025: Upskill

Apr 16, 2025Gifts for Boyfriend: What Women Are Asking Online?

Apr 16, 2025Top Real Estate Broker Software to Power Smarter

Apr 16, 2025How a Psychiatrist Can Help You Improve Mental

Apr 16, 2025How to Dress Up or Down the Essentials

Apr 15, 2025How to Choose the Best Audio Recorder for

Apr 15, 2025Why Now Is the Best Time to Explore

Apr 15, 2025Global 3D Printing Gases Market Set to Soar

Apr 15, 2025Mitolyn in New York: Ultimate Guide Weight Loss

Apr 15, 2025Top Reasons to Choose a 4-Star Hotel in

Apr 15, 2025Global Nutritional Analysis Market Set to Soar by

Apr 15, 2025How to Use GMB Everywhere? Complete Guide to

Apr 15, 2025From Romantic Getaways to Paint Nights – Gifting

Apr 15, 2025Top Brightening Face Scrubs to Try in 2025

Apr 15, 2025Vibe Experience Gifts – Adventures, Art, Food &

Apr 15, 2025Taking Care Of Health & Beauty at Our

Apr 15, 2025The Future of Healthcare: Why AI Mobile Apps

Apr 15, 2025Does Body Filler Treatment Require Anesthesia?

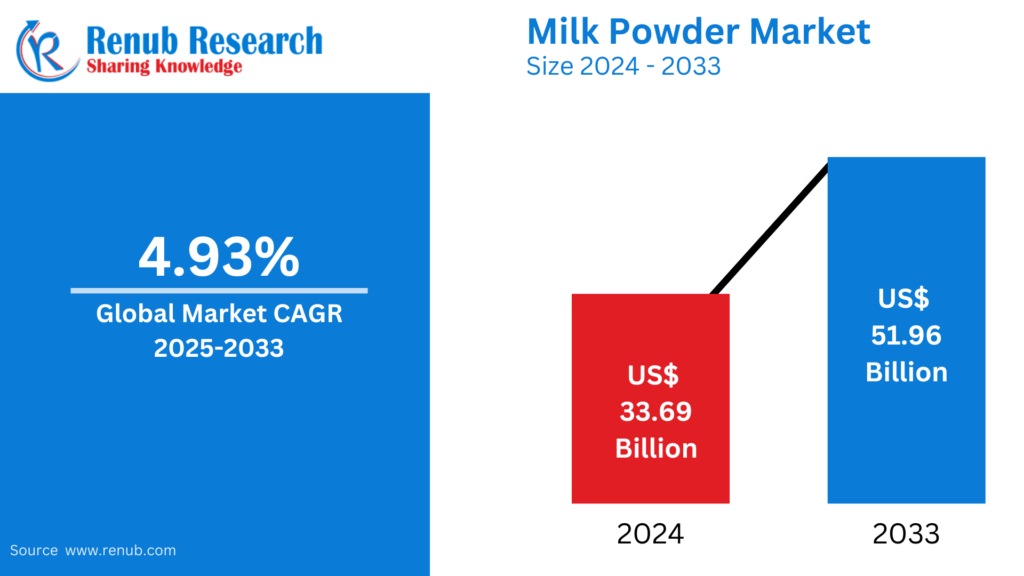

Apr 15, 2025Milk Powder Market : Key Drivers, Regional Insights

Apr 15, 2025Benefits of Choosing a Birthing Center in Tulsa

Apr 15, 2025Dump Trucks & Mining Trucks Market : Key

Apr 15, 2025How the Broken Planet Hoodie Scuplts Distinction

Apr 15, 2025Imported Japanese Diapers & Baby Food at Kurumi

Apr 15, 2025Your Trusted Online Shop for Baby Goods from

Apr 15, 2025Understanding the Role of a Neurologist in Treating

Apr 15, 2025Why You Should Host Your Next Event at

Apr 15, 2025Styling Tips for Korean-Inspired Outfits

Apr 15, 2025Anti-Aging Tips Using Natural Ingredients

Apr 15, 2025How’s the Intel i7 vPro Platform Supporting Remote

Apr 15, 2025Recruitment agency in delhi – hirex

Apr 15, 2025Is Natural Cotton Batting the Best Choice for

Apr 15, 2025Private Taxi from Leeds to Manchester Airport –

Apr 15, 2025Best PPC Company in India for Better ROI

Apr 15, 2025How a Top Video Production Agency is Scooping

Apr 15, 2025B2B Payments in 2025: Emerging Trends and Payment

Apr 15, 2025Navigating Global Trade: How Dubai Became a Shipping

Apr 15, 2025Warren Lotas Hoodie: Exclusive Streetwear

Apr 15, 2025Electric Kick Scooter Market : Insights & Forecast

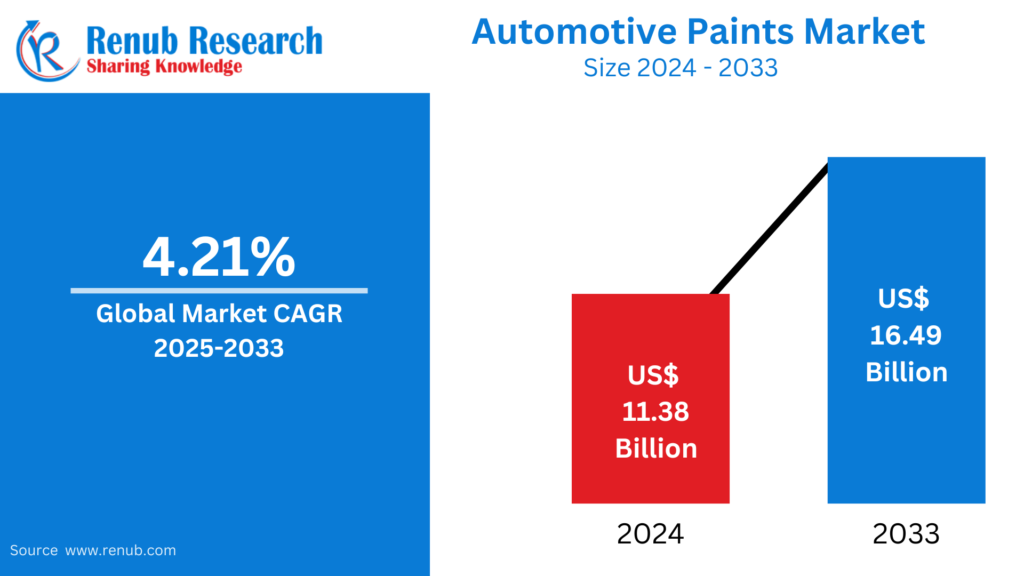

Apr 15, 2025Automotive Paints Market : Insights & Forecast to

Apr 15, 2025Causes of Irregular Periods in Your 30s

Apr 15, 2025Avoiding Common Mistakes When Applying for a Vehicle

Apr 15, 2025Find Premium Home, Beauty, and Health Products at

Apr 15, 2025Shop Quality Products for Every Aspect of Your

Apr 15, 2025Daily Current Affairs in Telugu

Apr 15, 2025Reputable Car Engine Repair: Best Service Practices

Apr 14, 2025MRCOG Part 1 Dates Revealed: What Every Candidate

Apr 14, 2025Is Your Office Lock Jammed? Hire a Locksmith

Apr 14, 2025AZ-104 Exam Dumps: Microsoft Azure Administrator QnA

Apr 14, 2025Why Choosing the Right Audit Company Matters for

Apr 14, 2025Business Travel to Kenya: Visa Rules, Validity, and

Apr 14, 2025Why Spaghetti Strap Blouses Are a Must-Have in

Apr 14, 2025Cheap Taxi from Leeds to Manchester Airport with

Apr 14, 2025The Ultimate Guide to Local SEO for Small

Apr 14, 2025Free 6 Tips: Learn How to Use a

Apr 14, 2025Top Crops for Small-Scale Farming: A Brief Guide

Apr 14, 2025What Are the Key Pieces of Computer Networking

Apr 14, 2025Best Kodi Alternative for iOS in 2025

Apr 14, 2025How do you find the perfect nose shape

Apr 14, 202511 iPhone 12 Case Cover for Nature Lovers

Apr 14, 2025Where to Buy Snore Stop Products Online and

Apr 14, 2025Top Reasons to Choose Thailand for Your Next

Apr 14, 2025Coffee Beans Market is Set to Witness Significant

Apr 14, 2025Snack Food Market is Projected to Reach USD

Apr 14, 2025Vegetable Oil Market to Reach USD 790,878.03 Mn

Apr 14, 2025Abrasive Market Will Achieve USD 63.79 Billion by

Apr 14, 2025Instant wellness? Try home-based IV therapy in Dubai

Apr 14, 2025Are There Programs That Offer Housing Help for

Apr 14, 2025How Noise-Canceling Earbuds Enhance Your Focus

Apr 14, 2025Steps to Purchase from Sp5der Hoodie Brand

Apr 13, 2025MERTRA || Shop Now Mertra Mertra Clothing ||

Apr 13, 2025Understanding Different Types of Teens Counselling

Apr 13, 2025Experience at Hellstar T-Shirt Online Official Store

Apr 13, 2025MERTRA || Shop Now Mertra Mertra Clothing ||

Apr 13, 2025Top 10 Natural Remedies for Insomnia That Help

Apr 13, 2025Where Purpose Meets Action: A Look at Local

Apr 13, 2025How to Find the Right Healthcare Support During

Apr 13, 2025LANVIN® || Lanvin Paris Official Clothing || New

Apr 12, 2025Bape Shirt: Thoughtful Design for Comfort and Style

Apr 12, 2025Ultimate Tips To Boost Your Academic Scores in

Apr 12, 2025The Top 7 Reasons Why Your Car Needs

Apr 12, 2025South Africa Visa Processing Time: What to Expect

Apr 12, 2025Rehydrate, Energize, Glow – All with IV Therapy

Apr 12, 2025Falsely Accused of Domestic Violence? How to Find

Apr 12, 2025Corteiz ® | CRTZRTW Official Website || Sale

Apr 12, 2025Simplify Complex Tasks with MATLAB Assignment Help

Apr 12, 2025Exploring Bare Metal Cloud Market Growth: Trends &

Apr 11, 2025The Ultimate Guide to Quick and Easy Car

Apr 11, 2025Why Use React Helmet for Managing Page Titles

Apr 11, 2025Best Pool Parties in Dubai and Best Beach

Apr 11, 2025Finding the Best Psychologist in Dubai A Guide

Apr 11, 2025Look for Irish Assignment Help Services to Ensure

Apr 11, 2025¿Vale la pena el trasplante de pelo precio?

Apr 11, 2025Tired of Hair Loss? Discover the Magic of

Apr 11, 2025The Importance of Tile Glue and Waterproofing in

Apr 11, 2025Best Therapist in Dubai: Your Guide to Anxiety

Apr 11, 2025Transforming Dubai’s Infrastructure: An Overview

Apr 11, 2025Affordable Stockport Taxis – Book Your Reliable Ride

Apr 11, 2025Handcrafted Eco Baby Toys That Promote Learning |

Apr 11, 2025Saudi Arabia Chiller Market Growth, Key Trends &

Apr 11, 2025Discover Unmatched Comfort at the Best Resorts in

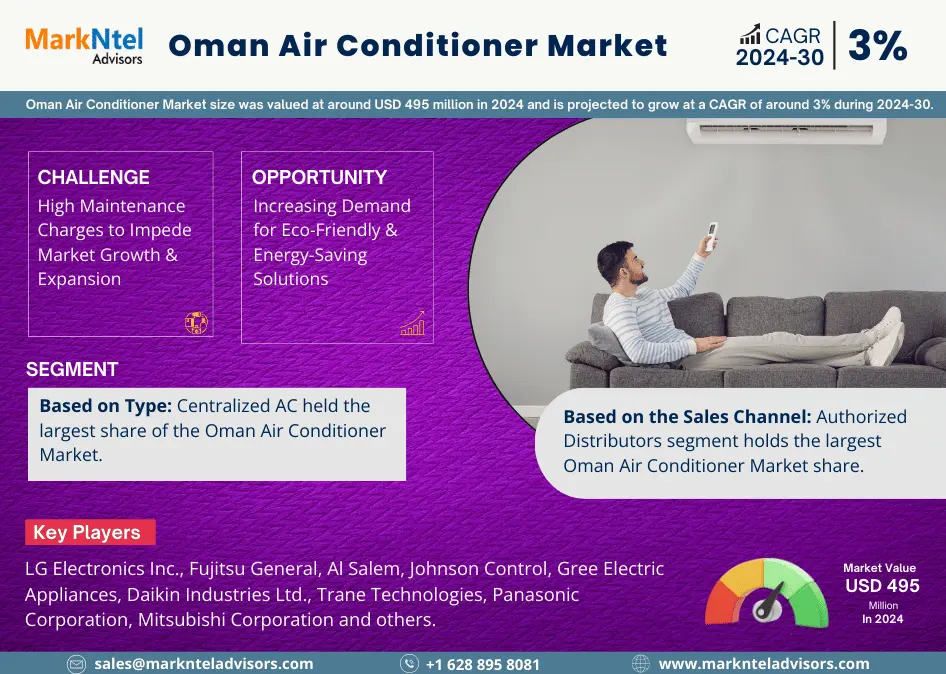

Apr 11, 2025Oman Air Conditioner Market Growth, Key Trends &

Apr 11, 2025Smart Camera Market : Key Drivers, Regional Insights

Apr 11, 2025Middle East and Africa Press Fit Connector Market

Apr 11, 2025Pranav International Oil Mill Machinery

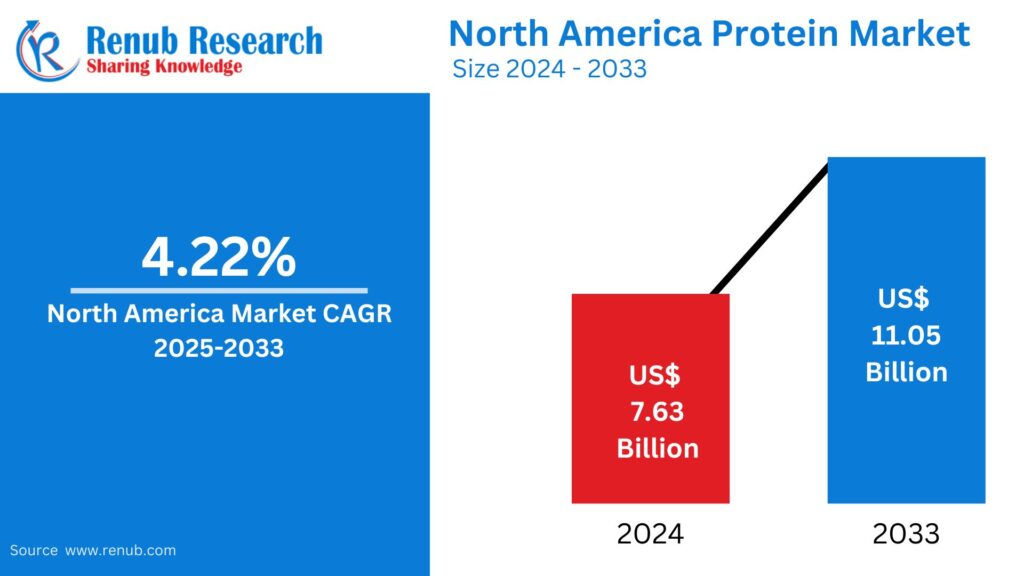

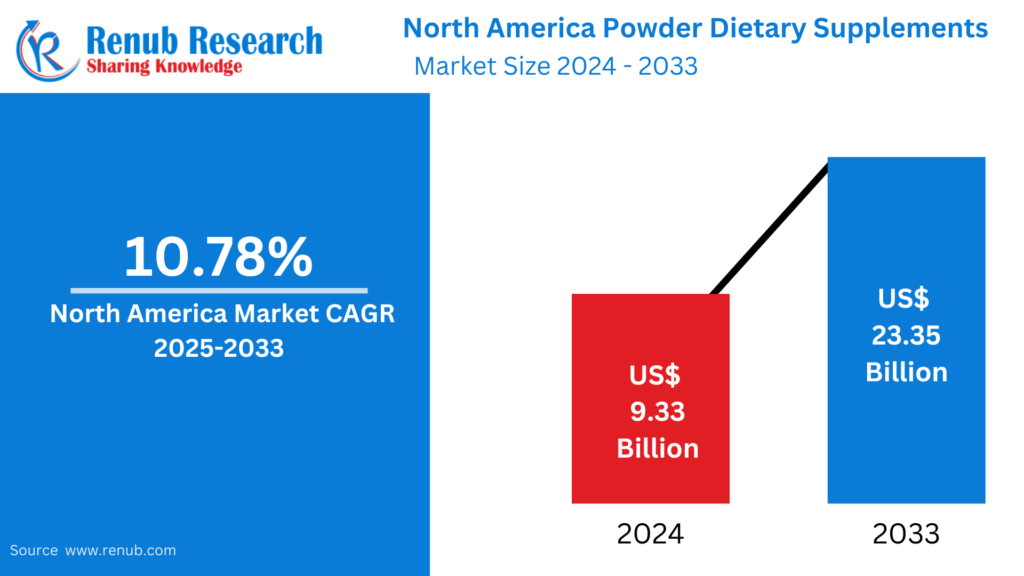

Apr 11, 2025North America Protein Market : Key Drivers, Regional

Apr 11, 2025Do Urinary Tract Infections Lead to Kidney Damage?

Apr 11, 2025Vegan Food Market: Key Drivers, Regional Insights &

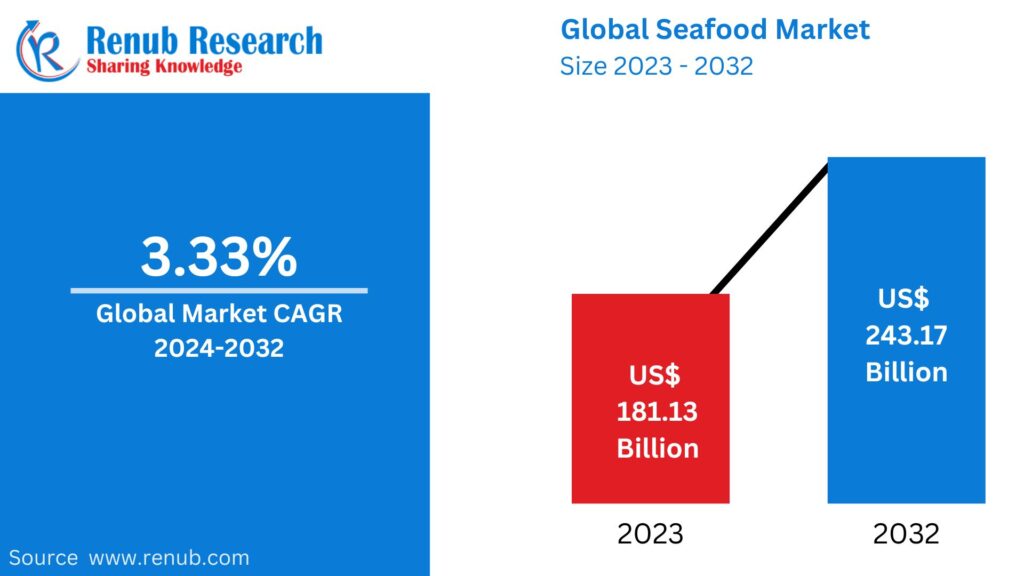

Apr 11, 2025Seafood Market : Key Drivers, Regional Insights &

Apr 11, 2025United States Small Kitchen Appliances Market : Key

Apr 11, 2025Mengapa Ligue 1 Jadi Tambang Emas bagi Pemandu

Apr 11, 2025Cortiez Cargos: The Streetwear Staple You Need in

Apr 11, 2025Google Shopping Feed Simprosys – Sync Inventory Fast

Apr 11, 2025Essentials Shorts: Comfort, Style, and Versatility

Apr 11, 2025Protect London® | Protect LDN Clothing Store |

Apr 11, 2025Protect London® | Protect LDN Clothing Store |

Apr 10, 2025Mertra Uk || MertraMertra Clothing || Online Shop

Apr 10, 2025The Best Guide to Home Security Camera Installation

Apr 10, 2025Evisu Shirt: Thoughtful Design for Comfort and Style

Apr 10, 2025Medical Products for Clinics and Hospitals

Apr 10, 2025Denim Tears Shirt: Thoughtful Design for Comfort and

Apr 10, 2025How Long Does SEO Take to Deliver Results?

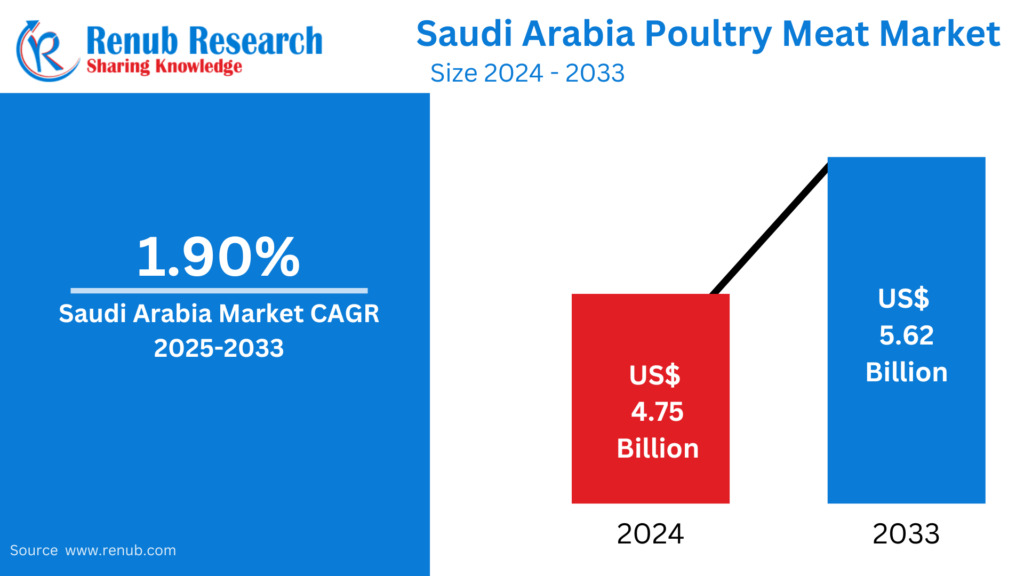

Apr 10, 2025Saudi Arabia Poultry Meat Market : Key Drivers,

Apr 10, 2025Menswear Market : Key Drivers, Regional Insights &

Apr 10, 2025Fire firms help Abu Dhabi businesses meet safety

Apr 10, 2025Child Care and Development: A Guide for Babysitters

Apr 10, 2025The Importance of a Mattress Protector for Your

Apr 10, 2025Car Insurance Dubai: The Importance of Add-ons

Apr 10, 2025Boost Business Safety & Appeal with Outdoor Lighting

Apr 10, 2025SEO Trends for 2025: What’s Changing?

Apr 10, 2025Best Floodlights Guide for Outdoor Spaces in Qatar

Apr 10, 2025Role of a Premier Security Service Company in

Apr 10, 2025The Importance of Timely Concrete Repair in Dubai’s

Apr 10, 2025IV Therapy in Dubai: The Ultimate Solution for

Apr 10, 2025Best Luxury Hotels In Shimla – A Royal

Apr 10, 2025Challenges Faced by Al Ain Contractors & How

Apr 10, 2025Why Investing in a Quality Gaming Chair in

Apr 10, 2025Why Do Events Need an Ambulance On-Site?

Apr 10, 2025How to Create a Cozy Yet Elegant Living

Apr 10, 2025Which Car Insurance is Mandatory in Abu Dhabi?

Apr 10, 2025How to Choose the Perfect Photo Studio for

Apr 10, 2025Male Infertility: Empowering Men to Seek Help and

Apr 10, 2025Commercial Golf Simulator: Cutting-Edge Technology

Apr 10, 2025How Paint Protection Film Saves Money in the

Apr 10, 2025Sleek & Stylish: The Allure of a Modern

Apr 10, 2025The Benefits of Raw Dog Food Diets: Is

Apr 10, 2025How to Manage Type 2 Diabetes Naturally

Apr 10, 2025How to Maintain Artificial Turf in the UAE’s

Apr 10, 2025How Yas Island is Redefining Sustainable Living in

Apr 10, 2025Top Yoga & Wellness Retreats in Dubai to

Apr 10, 2025Shisha & Fine Dining: Top Abu Dhabi Spots

Apr 10, 2025Choosing a Mobile App Developer in Abu Dhabi:

Apr 10, 20252025 Luxury Real Estate Trends: What Buyers Want

Apr 10, 2025Key Factors to Check Before Buying a Dubai

Apr 10, 2025The Hidden ROI of Custom Software: Beyond Just

Apr 10, 2025How Do You Choose the Perfect Gemstones for

Apr 10, 2025Inside TikTok’s Global Hubs: San Jose to Dubai

Apr 10, 2025Can IV Drips Help with Weight Loss?

Apr 10, 2025New Homes for Sale in Salem, Oregon: Affordable

Apr 10, 2025GV GALLERY® || Raspberry Hills Clothing Store ||

Apr 10, 2025Top Natural Wonders to See in Argentina

Apr 10, 2025Why Jacket Designer Are the Unsung Heroes of

Apr 10, 2025Embrace Culture with Stylish Desi T-Shirts

Apr 10, 2025Eco-Friendly Home Renovation Ideas for Chennai Homes

Apr 10, 2025Why Aluminium Doors & Windows Are Perfect for

Apr 10, 2025Do Dham Yatra by Helicopter – A Divine

Apr 10, 2025Transform Your Floors with Our Carpet Cleaner in

Apr 10, 2025Discover the True Cost of Manaslu Circuit Trekking

Apr 10, 2025Men’s Amethyst Bracelet: Bold, Stylish, and Full of

Apr 10, 2025The Best J.League Stadiums for Live Match Experience

Apr 10, 2025Host Nations That Overachieved at the World Cup

Apr 10, 2025Controversial VAR Decisions That Shook Up World Cup

Apr 10, 2025Reaksi Fan Tergila Setelah Gol di Dunia Football

Apr 10, 2025Вашият път към колата от САЩ започва с

Apr 09, 2025Купете автомобил от САЩ лесно и сигурно с

Apr 09, 2025Бързо и безопасно закупуване на автомобил от САЩ

Apr 09, 2025Търгове на автомобили в САЩ – директно до

Apr 09, 2025The Greatest World Cup Matches of All Time

Apr 09, 2025Top Football Nicknames and the Stories Behind Them

Apr 09, 2025Ride Expert-Tested MTB Routes on Fully Guided Tours

Apr 09, 2025Challenging & Scenic MTB Adventures in Europe and

Apr 09, 2025Royal Enfield Bullet 350 With A Ride Through

Apr 09, 2025Unlock Your Future with ACCA Online Courses in

Apr 09, 202510 Reasons to Work with an Email Marketing

Apr 09, 2025How to Match Socks to Your Outfit: A

Apr 09, 2025Recruitment agency in delhi-hirex

Apr 09, 2025Top 10 Trade Show Stand Design Ideas in

Apr 09, 2025Get Funding From Your Investments with a Loan

Apr 09, 2025Furnished Office for Rent in Dubai

Apr 09, 2025Singapore Airlines Bid for Upgrade – How to

Apr 09, 2025Kombiner sport og natur med de bedste MTB

Apr 09, 2025MTB ture i Danmark og Europa – eventyret

Apr 09, 2025The Ultimate Guide to Corteiz: Corteiz Cargos and

Apr 09, 2025Billionaire Boys Club: A Stylish Journey into Luxury

Apr 09, 202510 Questions to Ask Before Hiring a Roofing

Apr 09, 2025Stay Hydrated & Invincible with IV Drip at

Apr 09, 2025Why Kotlin is the Future of Android App

Apr 09, 2025Corporate Health Insurance vs Individual

Apr 09, 2025Insurance Agent Registration: A Step-by-Step Guide

Apr 08, 2025How a Georgetown Mortgage Broker Can Simplify Your

Apr 08, 2025The Mortgage Renewal Process In Calgary: What Should

Apr 08, 2025How Mortgage Brokers in Calgary Can Help You

Apr 08, 2025Human Touch in a Digital World: How Brands

Apr 08, 2025Membranes Market Estimated to Experience a Hike in

Apr 08, 2025How Can Essay Help Improve Grades

Apr 08, 2025Choosing a transparent aligners clinic: What are the

Apr 08, 2025How a Mobile App Development Company Can Boost

Apr 08, 2025Taxi from Manchester to Gatwick Airport – Reliable,

Apr 08, 2025How to choose the best options for industrial

Apr 08, 2025Find Hope and Healing at Our Texas Mental

Apr 08, 2025Cancer Daily Horoscope: Your Cosmic Guide for the

Apr 08, 20259 Reasons IoT is the Future of Mobile

Apr 08, 2025The Origin and Meaning of the Name Cortiez

Apr 08, 2025Reliable Solar Systems for Your Home and Business

Apr 08, 2025signers for sacoche trapstar

Apr 08, 2025How to Find Affordable and Reliable Maid Services

Apr 08, 2025Is Your PC Smarter Than You Think? Meet

Apr 08, 2025Why Every Business Needs a Barcode for Product

Apr 08, 2025Top Skin Clinic in Pune | Dermatologist &

Apr 08, 2025The Benefits Of A Gear Hob Manufacturers

Apr 08, 2025Refinance Mortgage: A Smart Move for Homeowners

Apr 08, 2025Nizoral 2 Percent Guide and Use – Your

Apr 08, 2025Uses of Sports Nets: Essential Gear for Various

Apr 08, 2025Pulled Hamstring Treatment: How to Heal and Recover

Apr 08, 2025Fast & Reliable Local Window Repair Experts

Apr 07, 2025How Virtual Offices in Tulsa Reshape the Future

Apr 07, 2025Choosing the Right SEO Services in Columbus, Ohio

Apr 07, 2025Your Destination for Japanese Beauty Essentials

Apr 07, 2025Tennis Court Cost: What You Should Expect in

Apr 07, 2025Top 7 Home Buying Mistakes to Avoid in

Apr 07, 2025Securing the Cloud: A Deep Dive into VMware

Apr 07, 2025Custom Stairs and Railings by Ora, Featuring Black

Apr 07, 2025The Pros and Cons of a Tankless Water

Apr 07, 2025Natural Yoga Asanas for Hair Growth and Strength

Apr 07, 2025Sovereign Debt & Emerging Markets

Apr 07, 2025The Ultimate Guide to British IPTV: A Smart

Apr 07, 2025Russia Wine Market Trends Forecast 2025-2033

Apr 07, 2025Elevate Your Style with Pakistani Clothes Online –

Apr 07, 2025Gemini Daily Horoscope: Your Guide to the Stars

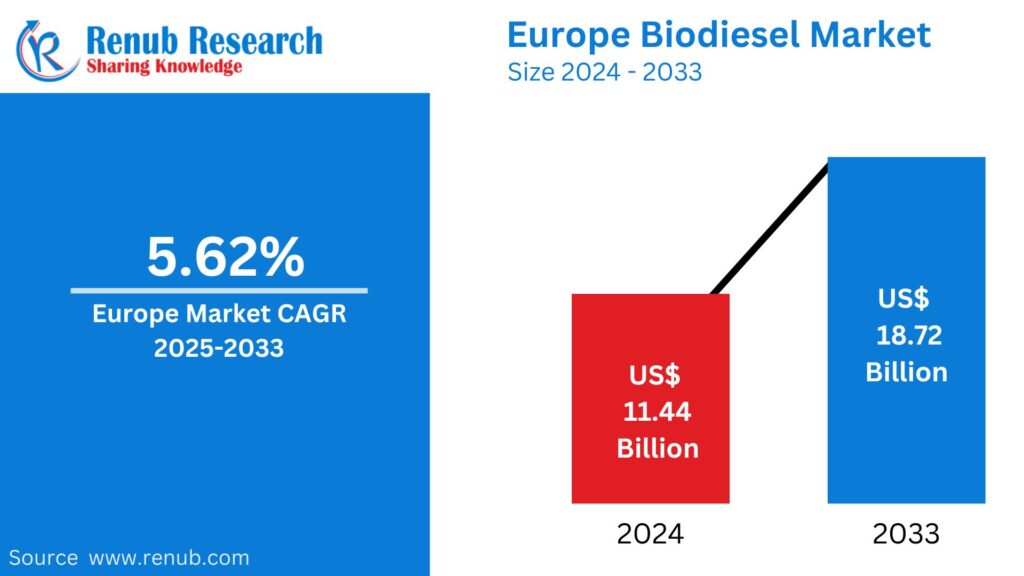

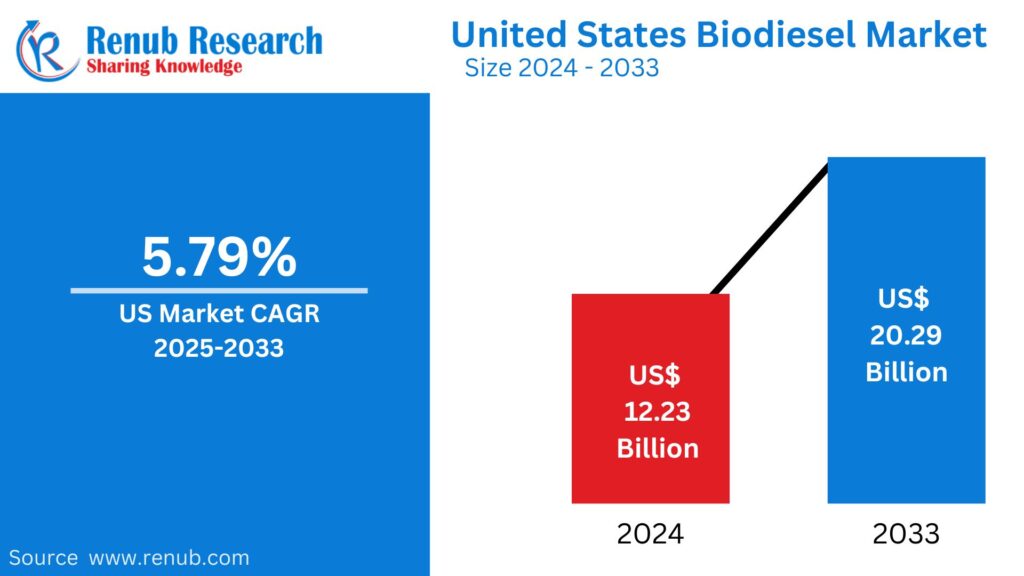

Apr 07, 2025Europe Biodiesel Market Trends Forecast 2025-2033

Apr 07, 20253 Ply Single Wall Custom Corrugated Boxes Supplier

Apr 07, 2025Tissue Paper supplier Everything You Need to Know

Apr 07, 2025United States Soup Market Trends Forecast 2025-2033

Apr 07, 2025The Tactical Evolution of RB Leipzig in 2025:

Apr 07, 2025Top 10 Must-See Bundesliga Goals That Define Modern

Apr 07, 2025Achieve a Flatter, Firmer Abdomen with Tummy Tuck

Apr 06, 2025The Pegador Hoodie OF Urban Fashion

Apr 06, 2025Elevate Your Wardrobe with Vertabrae clothing

Apr 06, 2025What Makes Valabasas Jeans So Popular?

Apr 06, 2025What Makes Essentials Clothing So Popular?

Apr 06, 2025Why syna world tracksuit Is a Perfect Summer

Apr 06, 2025Use the Newest Trends from Madhappy sweatpants to

Apr 06, 2025What Makes corteiz clothing So Popular

Apr 06, 2025How to Get Unlimited Lives in Gardenscapes (2024

Apr 06, 2025The Ultimate Guide to Buying the Perfect Puzzle

Apr 06, 2025The Ultimate List of Prehistoric Combat (2024)

Apr 06, 2025The Mortgage Renewal Process in Courtenay: What You

Apr 06, 2025The Mortgage Renewal Process in saint john-What You

Apr 06, 2025No Surgery, Just Shape—Butt & Body Fillers That

Apr 05, 2025How To Prepare For Management Exams

Apr 05, 2025Septic Tank Service Greeley – Professional Cleaning

Apr 05, 2025Jewellery Business in India – SiriusJewels Franchise

Apr 05, 2025Top Realtors in Johnstown | Buy & Sell

Apr 05, 2025Longmont Solar Installation – Save Big with Solar

Apr 05, 2025Essential Tree Maintenance Tips for a Healthier Yard

Apr 05, 2025Glass Repair Denver | Residential & Commercial Glass

Apr 05, 2025Corteiz Clothing Review – Hype or Reality?

Apr 05, 2025Residential Carpet Cleaning – Keep Home Fresh and

Apr 05, 2025Dead Body Ambulance Services in Delhi: Process, Cost

Apr 05, 2025The Most Trusted IVF Centres in Pitampura for

Apr 05, 2025How to Claim Housing Disrepair Compensation in the

Apr 05, 20251977 Essentials Hoodie The Ultimate Comfort

Apr 05, 2025Box Printing in UAE: Your Ultimate Guide to

Apr 05, 2025How to Get Cheap Flights Last Minute: Top

Apr 04, 2025How to Find the Best Body Massage in

Apr 04, 2025The Offsite EMS Lead Auditor Course: Your Next

Apr 04, 2025Pea Protein Market Size, Report and Forecast |

Apr 04, 2025Step Up Your Sustainability Game with ISO 14001

Apr 04, 2025Stata Assignment Help Tips To Overcome Hurdles In

Apr 04, 2025Mitolyn® | Official Website | 100% Natural &

Apr 04, 2025How to Become a Pro Trader with ICFM’s

Apr 04, 202510 Picturesque Spots in Kilkenny to Visit This

Apr 04, 2025Sell Used iPhone 14 for Cash: Get the

Apr 04, 2025Hire a Professional Packers and Movers Service in

Apr 04, 2025Interior & Exterior House Painters in Adelaide: What

Apr 04, 2025Mertra Uk || MertraMertra Clothing || Online Shop

Apr 03, 2025Florist Doreen: Heartfelt Flower Delivery

Apr 03, 2025MERTRA || Shop Now Mertra Mertra Clothing ||

Apr 03, 2025How Assignment Help in Australia Improves Your Study

Apr 03, 2025Order Funeral Flowers in Cyprus – Fast &

Apr 03, 2025The Role of WeldSaver 5 Passport in Modern

Apr 03, 2025Boris Johnson on Global Shifts at AIM Summit

Apr 03, 2025Personal Loan Interest Rate: Factors That Affect How

Apr 03, 2025Microneedling in Los Angeles: The Secret to Flawless

Apr 03, 2025Society in Central Delhi at The Amaryllis by

Apr 03, 2025Join ICFM Best Stock Market Institute for Traders

Apr 03, 2025Healthy Eating is Within Easy Reach With A

Apr 03, 2025Top Benefits of Choosing Home Delivery Food for

Apr 03, 2025Giorgio Milano’s Commitment to Affordable Luxury

Apr 02, 2025The Ultimate Guide to Booklet Printing: How to

Apr 02, 2025Why Ecommerce App Developers are the Backbone of

Apr 02, 2025How to Fundraise for a Cancer Charity in

Apr 02, 2025Taxi Transfers from Carlisle to Manchester Airport –

Apr 02, 2025The Essential Guide to Lock Pins: Uses, Types,

Apr 02, 2025Stay on Top of Your Billing: The Ultimate

Apr 02, 2025DFD: Your Professional Solution for Mold and Fungi

Apr 02, 2025Dates Market: Size, Share, Growth and Forecast |

Apr 02, 2025Infinity Glow: Lab-Created Diamond Wedding Band

Apr 02, 2025Best Movie Sites Like Fmovies for Streaming Movies

Apr 02, 2025How a Computer Course Can Boost Your Resume

Apr 02, 2025Elevate Your Social Media Presence with GSK SMM

Apr 02, 2025How to Make SMART Financial Choices While Purchasing

Apr 02, 2025Core i5 Laptops in Pakistan: The Ultimate Guide

Apr 02, 2025Ultimate Guide to Picking the Perfect Ergo Office

Apr 02, 2025Ultimate Guide to Choosing the Dog Carrying Purse

Apr 02, 2025The Impact of Backlinks on Ecommerce SEO and

Apr 02, 2025The Growing Demand for Fiber Optics in Kenya’s

Apr 02, 2025Top Things to Do in Machu Picchu for

Apr 02, 2025Triund Trek: A Scenic Adventure in the Heart

Apr 01, 2025TDS on Property Purchase from NRI: Key Rules

Apr 01, 2025How to Choose the Right Two-Wheeler Loan Tenure

Apr 01, 2025How Do I Rank My Real Estate Listings

Apr 01, 2025Tax Saving FD Schemes for Senior Citizens

Apr 01, 2025What is NPS? A Complete Guide to the

Apr 01, 2025Send Stunning Flowers Today | BUKETEXPRESS

Apr 01, 2025What are mutual funds, and how do I

Apr 01, 2025Best Pediatric Oral Dental Clinic Near Me: A

Apr 01, 2025Elementor #17783

Apr 01, 2025A Comprehensive Guide To Using Home Loan Calculator

Apr 01, 2025Private Baby Scans in Edinburgh: Everything You Need

Apr 01, 2025Rock Paper Scissors Yellow Dress Trend Uncovered

Apr 01, 2025How Much Does Air Conditioning Repair in Las

Mar 31, 2025How to Choose the Right Fertility Doctor for

Mar 31, 2025Ukrainian Touch: Precision in Every Translation

Mar 31, 2025Neon Sign: A Timeless Trend in Modern Decor

Mar 31, 2025How to Identify Authentic Free Range Eggs at

Mar 31, 2025TAFE Assignment Help – Get Expert Assistance Today!

Mar 31, 2025How Does SAP S/4 HANA Support Human Resources

Mar 31, 2025Honda City: The Epitome of Style, Comfort, and

Mar 31, 2025Say Goodbye To Mascara – Lash Lounge in

Mar 31, 2025The Ultimate White Fox Hoodie Collection You Can’t

Mar 31, 2025Translation Services in Kyiv – Serving Ukraine for

Mar 30, 202550+ Languages with 750+ Skilled Translators

Mar 30, 2025Cooper Jewelry: Merging Tradition with Modern Styles

Mar 30, 202520+ Years of Trusted Translation Expertise in Kyiv

Mar 30, 2025Tout savoir sur l’abonnement Atlas Pro : Le

Mar 30, 2025Manfredi Jewelry’s 30th Anniversary Celebrations

Mar 30, 2025Benison IVF – The Best IVF Centre for

Mar 30, 2025Cost Analysis of Engagement Platforms

Mar 30, 2025Step Guide to Managing Your Server with OpenVZ

Mar 29, 2025Affordable & Quality Rural Universities in India

Mar 29, 2025Global Market of Shot Blasting Machine Manufacturers

Mar 29, 2025How to File a Small Claims Case in

Mar 29, 2025Shot Blasting Machine Manufacturers in India

Mar 29, 2025best exhibition stand designer in dubai

Mar 29, 2025Bad Friend: The Impact of Toxic Friendships

Mar 29, 2025Syna World Beanie: A Deeper Look into the

Mar 29, 2025Window Cleaning Services: Clarity and Shine for Your

Mar 28, 2025HPE Aruba AP-105: Perfect Wireless Access Point for

Mar 28, 2025Education Loan for Your Higher Studies in India

Mar 28, 2025Certificacion gmp: Why It Matters and How to

Mar 28, 2025Are AI Computers the Next Big Thing in

Mar 28, 2025How AI Computers Make Hiring Smarter and Faster

Mar 28, 2025Why an Insulated Patio Cover is the Best

Mar 28, 2025How Podshop Makes It Easy with a London

Mar 28, 2025The Importance of Using a Torque Wrench Socket

Mar 28, 2025The Future of Mobile Apps: Trends Shaping the

Mar 28, 202510 Must-Have Apps for Your Samsung A34 in

Mar 28, 2025The Science Behind the PSYCH-K® Experience: Fact or

Mar 28, 2025Best Laptops in Pakistan – A Comprehensive Guide

Mar 28, 2025How to Apply for ISO Certification Online: A

Mar 28, 2025ISO 9001 Certification: A Game-Changer for Logistics

Mar 28, 2025Off Plan Villa in Dubai: Hidden Investment Gems

Mar 28, 2025Discover Your Dream Home at Eldeco Trinity

Mar 28, 2025Why ISO Training Should Be Your Next Business

Mar 28, 2025Top 5 M4ufree Alternatives for Movie Streaming in

Mar 28, 2025Exploring Rogue Pouches Flavors: A Flavor for Every

Mar 28, 2025“Up In Flames | Up In Flames London

Mar 28, 2025Best Laptops in Pakistan for Every Need and

Mar 28, 2025“Download Tiranga Game – Experience Ultimate Fun and

Mar 28, 2025The Purrfect Accessory for Your Phone

Mar 28, 2025Warehouse Sizes & Costs in Dubai: A Complete

Mar 28, 20257 Reasons AI Enhances Video Game Development

Mar 28, 2025How to Create a Section 125 Plan Document

Mar 28, 2025Why Cereal Packaging Plays a Bigger Role Than

Mar 28, 2025Best Post Construction Cleaning Services, Omaha

Mar 27, 2025Discover Mussoorie, Rishikesh, and Jim Corbett

Mar 27, 2025Navigating Hair Restoration for Women: Your Path to

Mar 27, 2025Luxury 2-Bedroom Homes for Sale in Jumeirah Park

Mar 27, 2025Get Radiant Skin with Charcoal Scrub-Say Goodbye to

Mar 27, 2025Top Benefits of a Cashew Nut Shelling Machine

Mar 27, 2025Are You Trying to Get Better? Examine the

Mar 27, 2025Which Competencies Are Essential for Jobs as Python

Mar 27, 2025MP3Juice: Free Music Downloads and Fast Access to

Mar 27, 2025Top Hair Transplant Clinics in Delhi Finding the

Mar 27, 2025Why Every Koi Pond Needs a Koi Pond

Mar 27, 2025Boost your vitamin D Levels with this 10

Mar 27, 2025The Power of Planning: Utilising a Personal Loan

Mar 27, 2025The Hidden Advantages: Key Benefits of Investing in

Mar 27, 2025Essential Roofing Tips for Contractors & Homeowners

Mar 27, 2025Your Guide to Roof Replacement Costs in St.

Mar 27, 2025Wholesale Socks for All: Shop in Bulk &

Mar 27, 2025Heavy Duty Caster Wheels India: High Load &

Mar 27, 2025Top 7 Best Mortgage Options Offered By Dream

Mar 27, 2025“Regular Cleaning Services in Jenks, OK | T-Town

Mar 27, 2025Protect London || Protect LDN Official Website ||

Mar 27, 2025IV Therapy for Dehydration: A Fast and Effective

Mar 26, 2025How to Get the Best Couples Massage &

Mar 26, 2025Why is Pharma CRM software necessary for success

Mar 26, 2025Best Algo Trading Software India – Quanttrix Review

Mar 26, 2025Software Entwicklung Agentur Berlin

Mar 26, 2025Best Asthma Doctor in Delhi – Expert Care

Mar 26, 2025UPSC Daily Current Affairs Test Series 2025 by

Mar 26, 2025Benefits of Custom Printed PET Cups & Why

Mar 26, 2025Pet Stomach Endoscopy Cost: 10 Ways to Plan

Mar 26, 2025What’s a Simple and Easy Quilt Pattern for

Mar 26, 2025Conservative Podcasts Worth Listening To

Mar 26, 2025Steps to Select the Right Investors Title Insurance

Mar 26, 2025Bots Now Dominate the Web, and That’s a

Mar 26, 2025Taxi from Glasgow to Manchester Airport Transfer

Mar 26, 2025The Ultimate Guide to Finding the Best Internet

Mar 26, 2025Upgrade Your Equipment with Robust Cast Iron Wheels

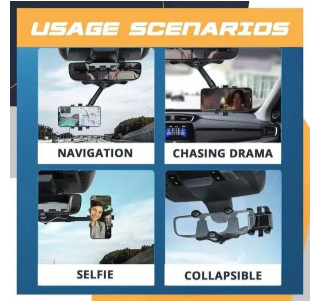

Mar 26, 2025How a Rotatable Car Phone Holder Improves Navigation

Mar 26, 2025How to Choose the Best Transport Company in

Mar 26, 2025Work-Life Balance Made Easy: from Laila Russian Spa

Mar 26, 2025The Odoo Support Ecosystem: Beyond the Basics

Mar 26, 2025KBH Games Pokemon Red: A Nostalgic Adventure for

Mar 26, 2025Why Does Krunker Keep Closing? Common Causes and

Mar 26, 202510 Reasons Why Turkey Tour is the Perfect

Mar 26, 2025Choosing thе Right Warеhousе Company in Dubai for

Mar 26, 2025Silk Dress: A Luxury Choice for Modern and

Mar 26, 2025Glass Cabinet Care Tips to Keep It Looking

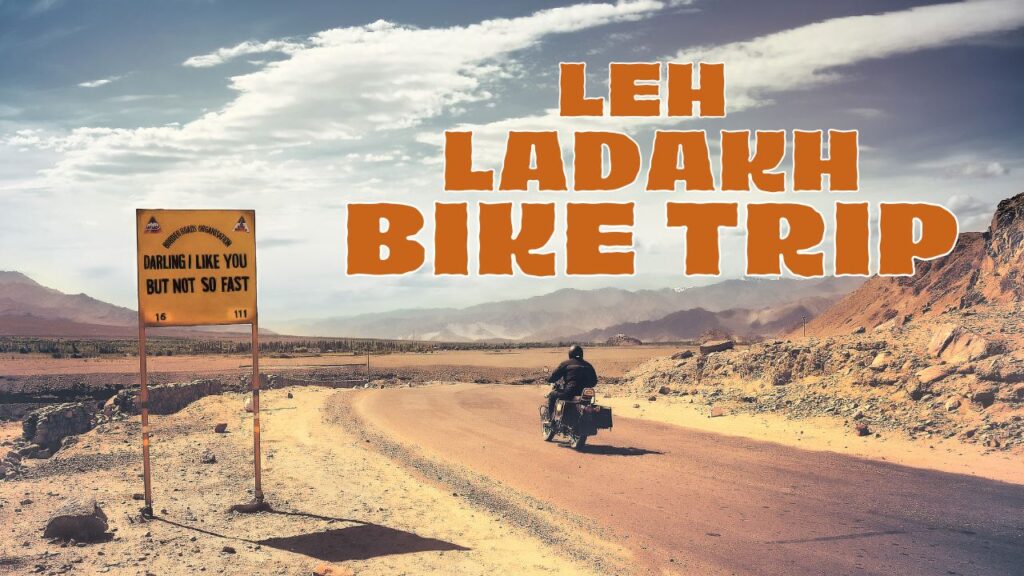

Mar 26, 2025Top 10 Adventure Activities to Try in Leh

Mar 26, 20256 Must-Have Technologies for Modern Gaming Monitors

Mar 26, 2025Test Box Strength with Pacorr’s Compression Tester

Mar 26, 2025Ginny and Georgia Season 3 Plot: Everything You

Mar 26, 2025HP Gaming Laptop: Power and Performance for Gamers

Mar 26, 2025Boost Performance: The Power of a Dedicated Linux

Mar 25, 2025Certification Services in Saudi Arabia

Mar 25, 2025Top 5 Data Analytics Tools for Business Intelligence

Mar 25, 2025Why General Dentistry Is Important for Your Oral

Mar 25, 2025ISO Certification in Pakistan: A Comprehensive Guide

Mar 25, 2025Turning Urban Garden Waste into Green Opportunities

Mar 25, 2025Ace Your Exams with Finance Assignment Help

Mar 25, 2025How to Manage Emergencies During a Leh Ladakh

Mar 25, 2025How to Plan a Scenic Road Trip Through

Mar 25, 2025How to Qualify for a Habitat for Humanity

Mar 25, 2025NAD+ IV Therapy for Hormonal Balance in Dubai

Mar 25, 2025Top 10 Features To Look for in a

Mar 25, 2025Why Penthouses in Qatar Are a Rare Investment

Mar 25, 2025How AI is Changing Recruitment & What Employers

Mar 25, 2025Vinyl vs. Wood Windows: Which is Better for

Mar 25, 2025Make informed decision while choosing to buy best

Mar 25, 2025Choosing the Right Dell 1U Rack Mount Server

Mar 25, 2025Trading on Autopilot: How AI is Reshaping the

Mar 25, 2025Best Multispeciality Hospital in South Delhi

Mar 25, 20256 Reasons to Buy an i5 Gaming Laptop

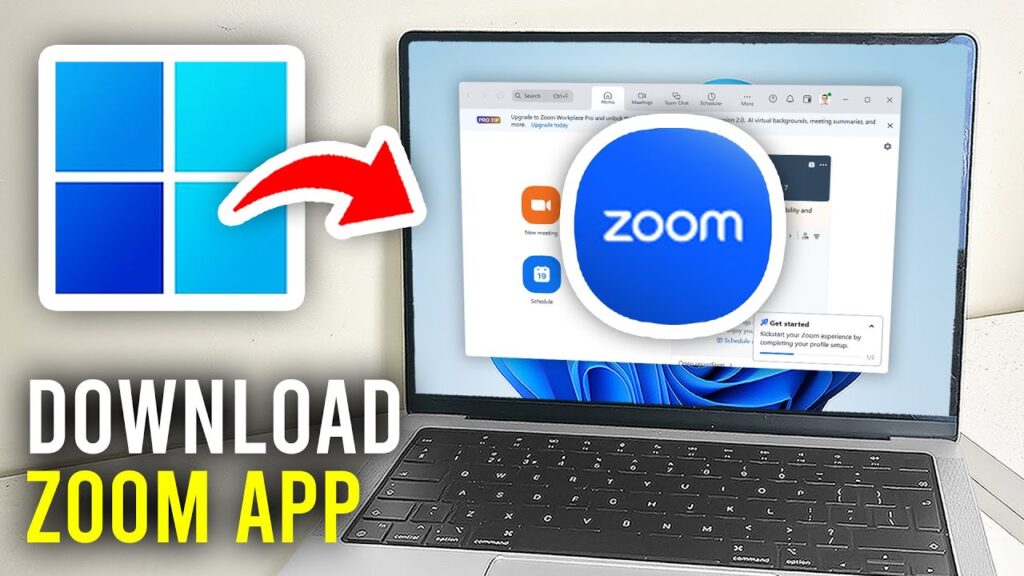

Mar 25, 2025Download APK Zoom for Laptop – Complete Guide

Mar 25, 2025Boost Your Poetry Career with a Professional Poetry

Mar 25, 2025Choosing the Best Editing Style for Your Athlete

Mar 25, 2025How Intel Arc Works with Intel Core for

Mar 25, 2025Best Massage Therapist in Minneapolis | Relax, Heal

Mar 25, 2025Lightweight vs. Hard-Shell: Which Carry-On is Best?

Mar 25, 2025Gaming Laptops: A Beginner’s Guide to Buying for

Mar 25, 2025What Advantages Do Professional Hair Curlers Offer

Mar 25, 2025Wind Damage on Your Roof? Call a Roofing

Mar 25, 2025The Cost Breakdown of Game Development Services

Mar 25, 2025Saint Vanity | Saint Vanity Shirt || Clothing

Mar 25, 2025Syna World: The UK Streetwear Label Taking Over

Mar 24, 2025Hellstar: The Streetwear Brand Taking Over the Game

Mar 24, 2025Syna World: The Streetwear Empire Shaping UK Fashion

Mar 24, 2025Drama Call: The New Wave of Suspense in

Mar 24, 2025Syna World: The Streetwear Empire Shaping UK Fashion

Mar 24, 2025NOFS: The Game-Changer in Modern Innovation

Mar 24, 2025Syna World: The Streetwear Empire Built by Central

Mar 24, 2025Syna World: The Streetwear Empire Taking Over the

Mar 24, 20255 Common Gym Mistakes & How to Avoid

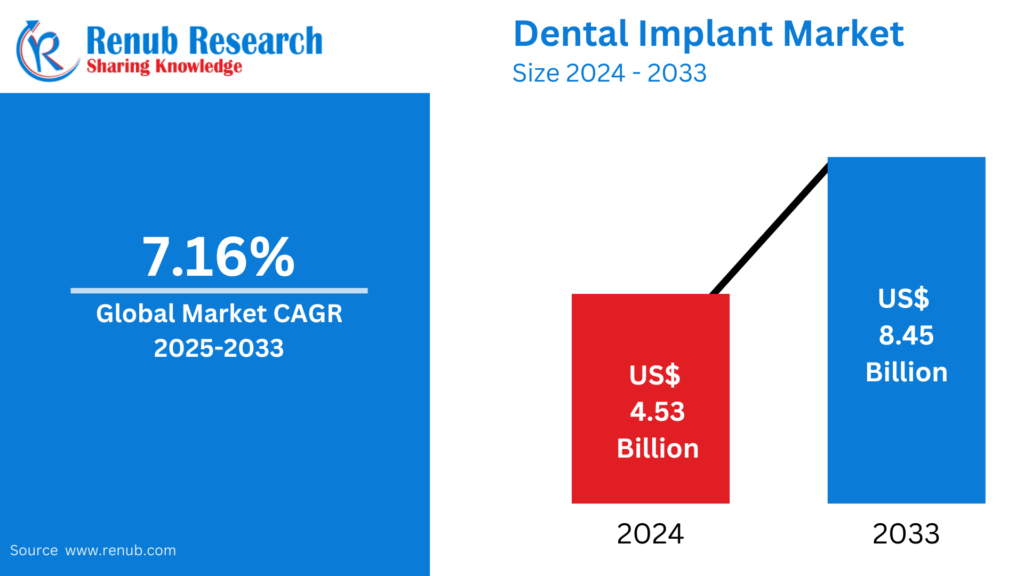

Mar 24, 2025Everything You Should Know About Dental Implants

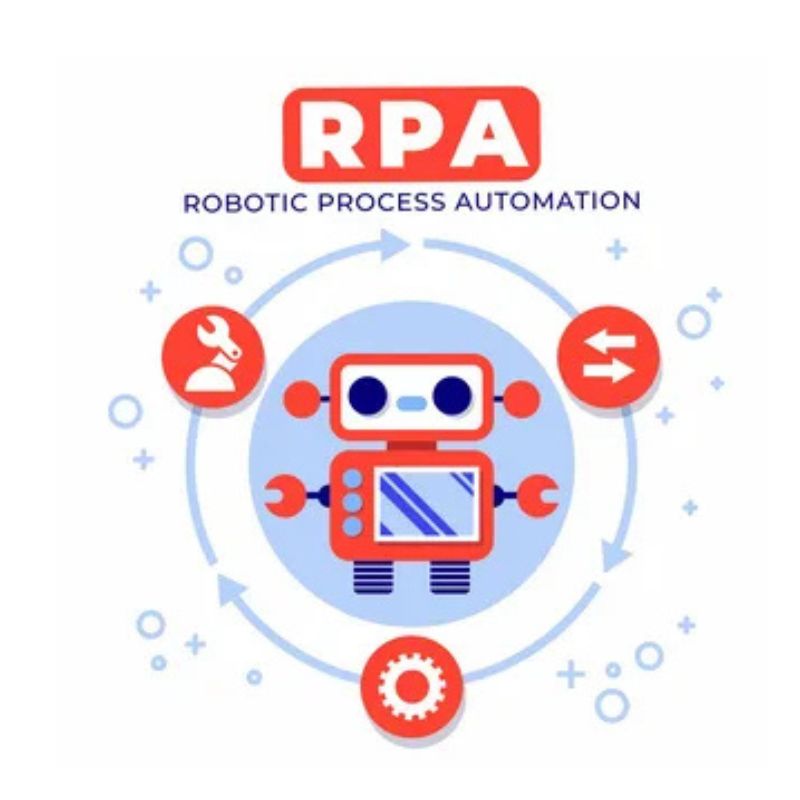

Mar 24, 2025Transform Your Business With Expert RPA Consulting

Mar 24, 2025Common challenges in research proposal writing

Mar 24, 2025United States Smart TV Market: Trends, Analysis &

Mar 24, 2025Vegetable Seeds Market : Trends, Analysis & Forecast

Mar 24, 2025Biopsy Devices Market : Trends, Analysis & Forecast

Mar 24, 2025Assessment Help Made Easy: Quality Support for Every

Mar 24, 2025How do you open a savings account online?

Mar 24, 2025United States Ice Cream Market : Trends, Analysis

Mar 24, 2025What Makes a Great Exhibition Stand Builder in

Mar 24, 2025Mexico vs. the U.S.: Why Luxury Homes in

Mar 24, 2025Is the YEEZY GAP Hoodie Worth the Investment or

Mar 24, 2025Discovering the Best Places to Eat in Houston

Mar 24, 2025Exploring Lamb Products: A Culinary Delight

Mar 24, 2025The Psychology Behind Home Visits: Why They Matter

Mar 24, 2025Malaysia Coffee Market : Trends, Analysis & Forecast

Mar 24, 2025Personalized Market By Renub Research

Mar 24, 2025Enhanced Analyst Support Services By Renub Research

Mar 24, 2025Social Research Services By Renub Research

Mar 24, 2025Mystery Audit Services By Renub Research

Mar 24, 2025Développé Épaule pour la Force et la Croissance

Mar 24, 2025The Ultimate Guide to Motorized Blinds in Qatar

Mar 24, 20252025 में तुर्की में घूमने की 10 बेहतरीन

Mar 24, 2025Why the USA Leads in Tech Salaries: Key

Mar 24, 2025Enhance Your Home Renovation with a Custom Sofa

Mar 24, 2025Best Garden Swing Cushions in Dubai – Enhance

Mar 24, 2025Dark Chocolate Market : Trends, Analysis & Forecast

Mar 24, 2025What to Look for in Stores That Sell

Mar 24, 2025Processed Meat Market : Trends, Analysis & Forecast

Mar 24, 2025Ice Cream Market : Trends, Analysis & Forecast

Mar 24, 2025Global Candle Market : Trends, Analysis & Forecast

Mar 24, 2025Europe Field Crop Seeds Market Share, Size, Growth

Mar 24, 2025Comprendre la CSRD et son rôle dans le

Mar 24, 2025Choosing the Right Trailer for Tiny Houses on

Mar 24, 2025Expert Help Assessment Services

Mar 24, 2025Hip Replacement Market : Trends, Analysis & Forecast

Mar 24, 2025Global Lipid Market : Trends, Analysis & Forecast

Mar 24, 2025United States Cheese Market : Trends, Analysis &

Mar 24, 2025Global Ginger Market : Trends, Analysis & Forecast

Mar 24, 2025Atlas Pro IPTV: The Ultimate Streaming Solution

Mar 24, 2025Atlas Pro ONTV: The Ultimate IPTV Streaming Solution

Mar 24, 2025IPTV Smarters PRO : La Solution Idéale pour

Mar 24, 2025Reliable Taxi from Sheffield to Manchester – Travel

Mar 23, 2025Warren Lotas | Warren Lotas Clothing | Official

Mar 23, 2025Everything You Need to Know About the Voopoo

Mar 23, 20256 Simple & Effective Ways to Nurture Your

Mar 23, 2025Global Ginger Market : Trends, Analysis & Forecast

Mar 22, 2025United States Video Game Market: Trends, Analysis &

Mar 22, 2025Hellstar gothic-inspired streetwear outfits”

Mar 22, 2025How to Use Rosemary Oil for Hair: A

Mar 22, 2025The Weeknd’s Presence in Fortnite’s Item Shop: A

Mar 22, 2025Who Is Travis Scott?

Mar 22, 2025MERTRA || Shop Now Mertra Mertra Clothing ||

Mar 22, 2025In Glock we trust hoodies are very stylish

Mar 22, 2025Adwysd joggers: The Pinnacle of Streetwear Elegance

Mar 22, 2025How to Find the Best Pest Control Companies

Mar 21, 2025The Role of Digital Solutions in Business Growth

Mar 21, 2025Essential Tips for a Seamless Carpet Installation in

Mar 21, 2025The Top 5 Stussy Hoodie Drops This Year

Mar 21, 2025Corteiz Hoodie Sizing Guide: Everything You Need to

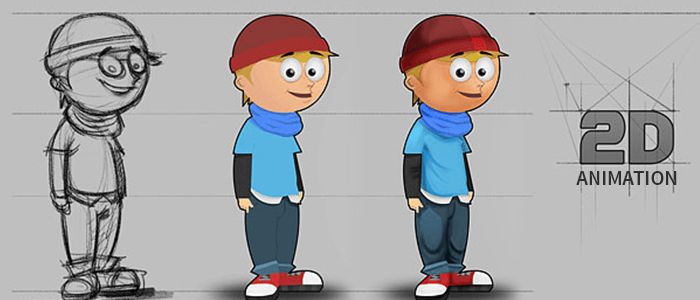

Mar 21, 2025How to Use 2D Animation Services in TikTok

Mar 21, 2025Gatwick to Manchester Airport Taxi – Reliable &

Mar 21, 2025Best Foods for Kidney & Bladder Health

Mar 21, 2025Why You Need a Family Law Attorney for

Mar 21, 2025Why Personal Loans Are The Best For Dental

Mar 21, 2025Best SSC Coaching in Delhi – BST Competitive

Mar 21, 2025Best Real Estate Investment Opportunities in 2025

Mar 21, 2025How to Score High with Management Assignment Help

Mar 21, 2025Guest Posting: A Powerful Strategy for Growth and

Mar 21, 2025Tips for Winning on an Online Sports Exchange

Mar 21, 2025How To Improve Your Credit Score With A

Mar 21, 2025How to Negotiate Rent Prices in Dubai?: Expert

Mar 21, 2025Can Home Painting Services in Dubai Increase Your

Mar 21, 2025Why Should You Choose Roller Blackout Curtains Abu

Mar 21, 2025Top Features to Look for in a Mosque

Mar 21, 2025Join Best CUET Coaching in Delhi – BS

Mar 21, 2025Best SP5DER Hoodie Outfits for Spring Vibes

Mar 21, 2025Wedding Photo Booth Sydney: Addition to Your Special

Mar 21, 2025How Niacinamide Serum Fights the Signs of Aging

Mar 21, 2025How To Boost Your Small Business With Social

Mar 21, 2025Choosing the Right Blue Carpet for Your Living

Mar 21, 202510 remarkable places to visit in Saudi Arabia

Mar 21, 2025Capitalize on the NFT Rewards Trend for Business

Mar 21, 2025Genesis Regenerative

Mar 21, 2025The Blowout Taper Fade: A Modern Twist on

Mar 21, 2025Elevate Your Look with Full Foil Highlights in

Mar 20, 2025How Private Label Toilet Cleaners Can Enhance Your

Mar 20, 2025Why Specialized Staffing is Crucial in the Software

Mar 20, 2025How to Choose the Right Curriculum for Your

Mar 20, 2025Smart Buying Guide: A4 Paper Prices and Suppliers

Mar 20, 2025How to Make an Uber Clone: A Complete

Mar 20, 2025Is the Traditional C-Spout Hot Water Faucet Worth

Mar 20, 2025Ever Read Your Medical Record? Here’s Why You

Mar 20, 2025Top 5 Demat Account Apps for Beginners in

Mar 20, 2025Best Perfume from Dubai: A Journey Through Luxury

Mar 20, 2025Get Audi back on the Road Fast with

Mar 20, 2025اجمل الروائح والعطور: سر الجاذبية والأناقة الخالدة

Mar 20, 2025Ryanair SKG Terminal 1 Guide – Check-in, Baggage

Mar 20, 2025Juice Supplier 101: Choosing the Right Partner for

Mar 20, 2025Where Can You Play Fantasy Cricket with Friends?

Mar 20, 20253D Sonography Center in Ahmedabad | Advanced Imaging

Mar 20, 2025Ayurveda Treatment for Bronchitis | Natural Healing

Mar 20, 2025Broccoli Low FODMAP? You Need to Know for

Mar 20, 2025Hellstar high-fashion meets street style

Mar 20, 2025Tips for Choosing the Right SEO Company in

Mar 20, 2025Build Your Own TikTok Clone App with Appscrip

Mar 20, 2025The Importance of Air Cargo Logistics Solutions in

Mar 20, 2025Boost Your Business with the Best San Francisco

Mar 20, 2025Why Retail Stores Are Adopting Digital AV Solutions

Mar 20, 2025Choosing a Local SEO Agency: Smart Steps for

Mar 20, 2025Where in Dubai Can you Find the Greatest

Mar 20, 2025CPA Tax Accountant & Tax Preparation Services by

Mar 20, 2025Top Free CAT Mock Tests to Crack 99+

Mar 20, 2025Common Pitfalls in Custom Software & Mobile App

Mar 20, 2025The Power of Executive Leadership Programs

Mar 20, 2025Outsourced IT and Helpdesk Services in Portland by

Mar 20, 2025Shell and Tube Heat Exchangers For Modern Industry

Mar 20, 2025Dog Birthday Cards: Make Your Pet’s Special Day

Mar 20, 2025The Ultimate Guide to Hiring Ruby on Rails

Mar 20, 2025How Much Does a Brand Naming Agency Cost?

Mar 20, 2025The Best Medical Scrubs and Accessories for Uni

Mar 20, 2025Efficient Freight Logistics for Business Success

Mar 20, 2025The Ultimate Guide to Diaper Baby Bags and

Mar 19, 2025The Future of Security with an Advanced Access

Mar 19, 2025How Nofs tracksuit benefit customers

Mar 19, 2025The impact of Cole Buxton pricing and promotions

Mar 19, 2025Best Supervisa Insurance for Parents & Visitors

Mar 19, 2025How All-in-one PC Save Purchase Costs

Mar 19, 2025AI / ML Development: Step-by-Step Guide to the

Mar 19, 2025Tips to Choose the Best Civil Lawyer

Mar 19, 2025Online Exam Help to Improve Your Scores

Mar 19, 2025How to Choose the Women’s Fragrance Oil for

Mar 19, 2025The Role of Packaging in Gum Brand Identity

Mar 19, 2025How To Convey Your Brand Message Through Packaging?

Mar 19, 2025Why Dual Microphone Laptops Are Ideal for Online

Mar 19, 2025Things to Remember About an Education Loan Interest

Mar 19, 2025Manchester to Heathrow Airport Taxi – Affordable &

Mar 19, 2025Why Is Sp5der the Most Popular Streetwear Brand?

Mar 19, 2025Safety Officer Course in Rawalpindi Islamabad

Mar 19, 2025Mumbai Airport: Terminal 1, 2 | Domestic &

Mar 19, 2025Crown Bar 8000 Puffs Vape by Vapeonic: An

Mar 19, 2025Role & Importance of Data Analytics in Healthcare

Mar 19, 2025Oxford Formal Shoes for Men – Timeless Elegance

Mar 19, 2025Navi Mumbai Airport: Terminal 1, 2 & 3

Mar 19, 2025Iran Air London Office in England

Mar 19, 2025What Makes Expert Caravan Cleaning Worth It?

Mar 19, 2025Why Is XPLR Merch So Popular Among Fans?

Mar 19, 2025The Top 8 Hot Air Balloon Rides in

Mar 19, 2025Lodha Meridian Kukatpally – Pros & Cons.

Mar 19, 2025How to Maintain the Packaging Machine?

Mar 19, 2025Best Solar Energy Company in Jamshedpur

Mar 19, 2025Godrej Kokapet – Brochure, Pros & Cons, Price

Mar 19, 2025Prestige Spring Heights Budvel – Pros&Cons .

Mar 19, 2025Brigade Gateway Neopolis Kokapet Hyderabad – Pros &

Mar 19, 2025Godrej Madison Avenue Kokapet Hyderabad – Pros &

Mar 19, 2025A Fusion of Elegance and Color: Pink Ruby

Mar 19, 2025Things To Consider While Buying Fence Panels In

Mar 19, 2025The Ultimate Guide to the Best Custom Neon

Mar 19, 2025A Step-by-Step Guide to Safely Hitching an Unbraked

Mar 19, 2025How to Choose the Right Weight Loss Medication

Mar 19, 2025Why Is Stussy So Popular in Streetwear Fashion?

Mar 19, 2025Corteiz Redefining Streetwear with Timeless Style

Mar 19, 2025GodSpeed Clothing || Official God Speed® Clothing ||

Mar 19, 2025The Importance of CCTV Installation in Fort Worth

Mar 18, 2025Rutchik and RIII Ventures launch Local Factor Group

Mar 18, 2025How Much Does it Cost to Hire a

Mar 18, 2025The Growing Demand for .NET Development and Its

Mar 18, 2025AI and 5G: The Future of Intelligent Networks

Mar 18, 2025Tips to Choose the Best Group Travel Limo

Mar 18, 2025Car Tire Repair Made Simple: Everything You Should

Mar 18, 2025The Amazing Benefits of Tube Expander Machines

Mar 18, 2025Tips to Choose the Best Impact Socket Suppliers

Mar 18, 2025Why Is Branding Important for Authors?

Mar 18, 2025Online CV Writers Services in UAE: Crafting Resumes

Mar 18, 2025Why You Need a Drop Tester for Packaging

Mar 18, 2025Homeopathy Courses: A Path to Natural Healing and

Mar 18, 2025Optimizing Workforce Management in Dubai

Mar 18, 2025Beginner Gamers Are Cashing In With The Daman

Mar 18, 2025Maximize Your Home Comfort with a 2-Zone Condenser

Mar 18, 2025How Businesses Can Meet Consumers in Today’s Digital

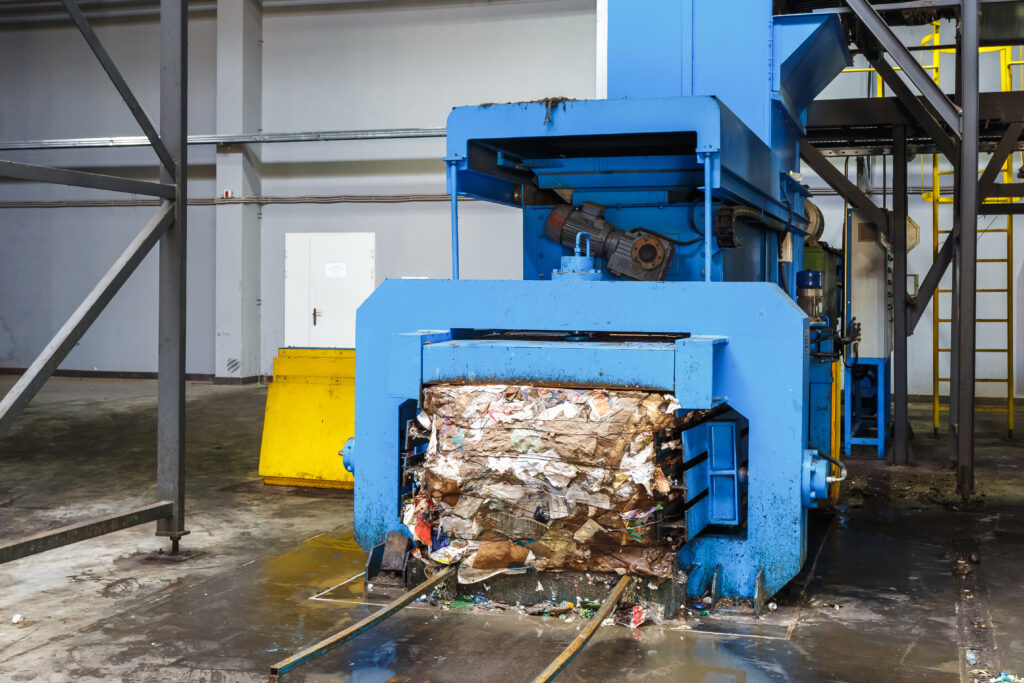

Mar 18, 2025The Ultimate Guide to Scrap Metal Removal: Recycling

Mar 18, 2025Exploring the Legacy of Parker Ballpoint Pens:

Mar 18, 2025How the Hood Cleaning Experts Program Prepares You

Mar 18, 2025How to Repair Holes and Rips in Your

Mar 18, 2025Everything You Need to Know About FUE Hair

Mar 18, 2025Big Basket Special Offers on Organic and Healthy

Mar 18, 2025Rain Gutters in New Orleans Protect Your Home

Mar 18, 2025What Are the Advantages of Trade Data?

Mar 18, 2025Artificial Intelligence: Revolutionizing the Future

Mar 18, 2025Best Joint Replacement Treatment in Lahore – Expert

Mar 18, 2025JOS Family Law

Mar 18, 2025Why Your Business Needs an Indian Digital Marketing

Mar 18, 2025Best Cool Tech Gadgets of 2025

Mar 18, 2025Var kan man få topprankade VVS-tjänster i Huddinge?

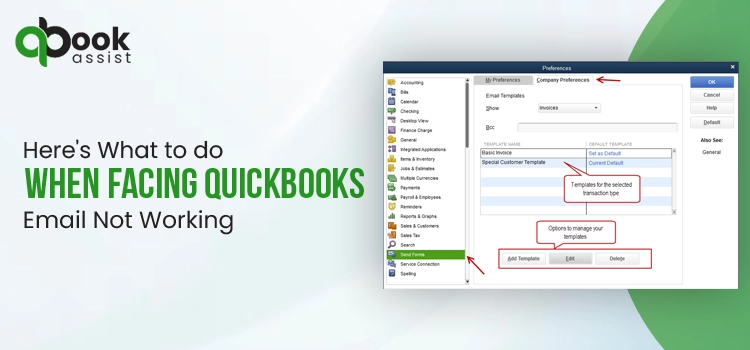

Mar 18, 2025How to Fix QuickBooks Email Not Working

Mar 18, 2025Professional Window Installation in Newton MA

Mar 18, 2025Building Estimation UK | Get the best Services

Mar 18, 2025Advanced Pet X-Ray & Diagnostics in Dubai |

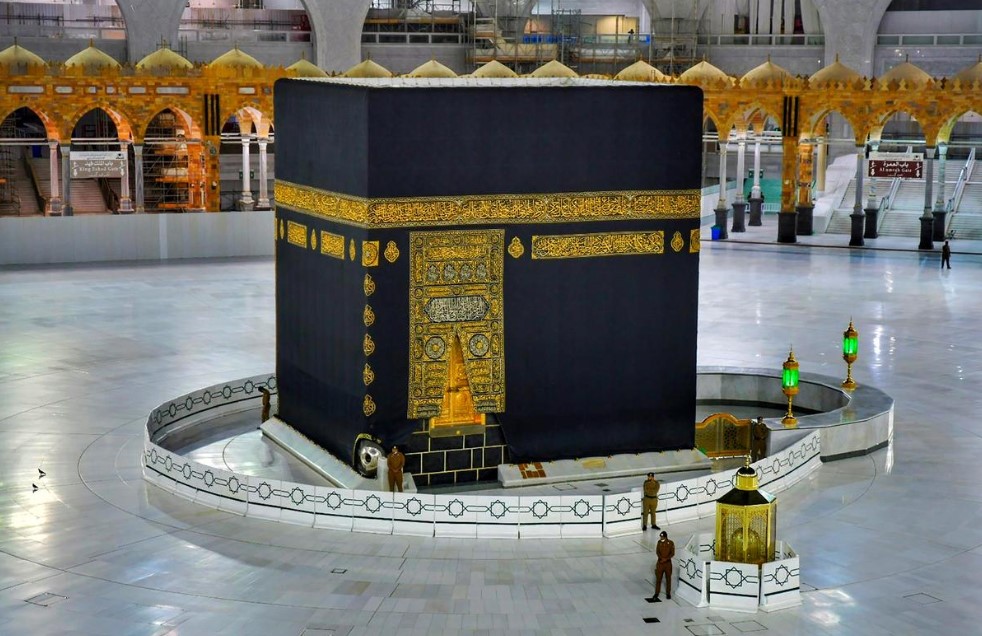

Mar 18, 2025Explore the Best Umrah Packages from the UK

Mar 17, 2025Role of a Technical Project Manager Scrum Master

Mar 17, 2025The Importance of Mock Tests in 11+ Creative

Mar 17, 2025Experion Sector 151 Noida | Step Into The

Mar 17, 2025Tips to Choose the Best Civil Engineering Online

Mar 17, 2025Your Ultimate Guide to Email Marketing Agency in

Mar 17, 2025Hydrogen Storage Market: Unlocking the Future

Mar 17, 2025Latest Digital Marketing Updates in 2025

Mar 17, 2025How to Prepare an Effective ESG Report: A

Mar 17, 2025How Can Mini Cooper Body Kits in Dubai

Mar 17, 2025Taxi from Manchester to Birmingham DING!

Mar 17, 2025Why Promotional Bags Are a Reliable Choice for

Mar 17, 2025Kubernetes vs Docker: Which One is Right for

Mar 17, 2025How to Choose the Right Industrial Door

Mar 17, 2025Enhance Your Floors in Auckland: Practical Tips for

Mar 17, 2025LED Signs for Business: Boost Your Brand and

Mar 17, 2025Why Choose Dr. Kris A. DiNucci? 6 Key

Mar 17, 2025“Choosing the Best Umrah Packages for a Hassle-Free

Mar 17, 2025How to Pick the Best Interior Company Dubai

Mar 17, 2025Why Your Company Needs Waste Disposal Software Today

Mar 17, 2025“Gift a Quran: A Meaningful and Spiritual Present”

Mar 17, 2025Fix Foot Pain Fast – With Top Podiatrist

Mar 17, 2025Double Marker Test: Purpose, Procedure, and Benefits

Mar 17, 2025Prepaid Wallet License Eligibility: What You Need to

Mar 17, 2025Bike Transport Service in Vadodara: Way to Relocate

Mar 17, 2025“Shop Diamond Rings for Women: Classic, Modern &

Mar 17, 2025Top PhD Thesis Writing Services in India –

Mar 17, 20256 Must-Have Features for Wedding Cars in Ambala

Mar 17, 2025Top 5 Indian Attar Perfumes You have to

Mar 17, 2025Why Microneedling with PRP is the Hottest Treatment

Mar 16, 2025Can Masonry Stain for Brick Protect Against Weather

Mar 16, 2025What Are the Benefits of Using a Podcast

Mar 16, 2025How to Make Business Cards: Guide to Creating

Mar 16, 2025Sapno Ki Bhasha: Chipkali Aur Uske Sanket

Mar 16, 2025Merino Wool Care: The Ultimate Guide to Keeping

Mar 16, 2025What Are the Best Cybersecurity Programs in Florida?

Mar 16, 2025Printable Materials for Candle Boxes with Inserts

Mar 15, 2025Effective Tips to Prevent Neck Pain

Mar 15, 2025Best Car Rental in Dubai – Luxury, Comfort

Mar 15, 2025Buy Trendy Chikankari Suits for Women

Mar 15, 20255 Signs Your Car Needs Professional Detailing in

Mar 15, 2025Best Solar Panel Installation Company in Jamshedpur

Mar 15, 2025Imperial Perfume: A Deep Dive into Its History,

Mar 15, 2025Common Misconceptions About Bitachon

Mar 15, 2025From Eye Care to Hair Growth: Bimatoprost

Mar 15, 2025Latisse: A Guide to Generic Latisse for Eyelash

Mar 15, 2025Find and Hire a Skilled Blogger and Blog

Mar 15, 2025The Impact of a Poor-Performing Battery

Mar 15, 2025Discover Exquisite Jewelry Design in Dorset

Mar 14, 2025synaworldsiteuk Official syna world Online Store

Mar 14, 2025The Alluring Essence of Arabian Perfume

Mar 14, 2025The Key Differences Between 2D and 3D Animation

Mar 14, 2025The Story Behind Mad Happy: Redefining Mental Health

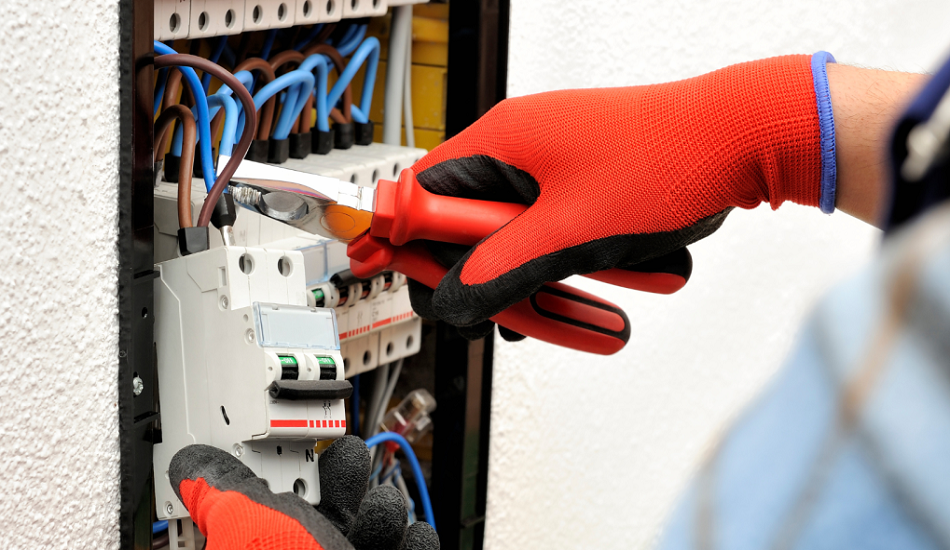

Mar 14, 2025The Role of a Professional Electrical Contractor

Mar 14, 2025How to Force Quit on Mac: A Step-by-Step

Mar 14, 2025How Projects Can Be Billed at Timesheet Hours

Mar 14, 2025Email Marketing Agency Arizona –

Mar 14, 2025What Makes Ultrasonic Testing Reliable?

Mar 14, 202510 Reasons to Work with an Email Marketing

Mar 14, 2025Guide to Traveling from Makkah Train Station to

Mar 14, 2025SEO Company : Driving Your Business to Digital

Mar 14, 2025Villa Deep Cleaning Services in Dubai: The Pristine

Mar 14, 2025Unlocking the Benefits of Pure Organic Shilajit

Mar 14, 2025The Ultimate Guide to Using a LaGuardia Airport

Mar 14, 2025Getting from Makkah Train Station to Haram by

Mar 13, 2025Best Cab Service to the Airport – Fast

Mar 13, 2025How To Extract Emails from Websites Without Getting

Mar 13, 2025Check the Legitimacy of a Property Before Lease

Mar 13, 2025How KVM VPS Hosting Supports Gaming Servers and

Mar 13, 2025Dairy and Organic Food: A Comprehensive Overview

Mar 13, 2025Mastering Forex Trading with Real-Time Market Data

Mar 13, 2025What Does a Vape Smell Like? Ultimate Guide

Mar 13, 2025Infinix Hot 50 Pro Plus Price in Pakistan

Mar 13, 2025How to Manage CRM Pipeline in Odoo 18

Mar 13, 2025Best Limousine Service in Morristown, NJ

Mar 13, 2025Car Unlock Service Abu Dhabi – 24/7 Professional

Mar 13, 2025The Ultimate Guide to Forex API: Access Real-Time

Mar 13, 2025Why Your Business Needs a B2B Email Marketing

Mar 13, 2025How To Take Care Of Your Leather Rifle

Mar 13, 2025Geography Optional at Tathastu ICS

Mar 13, 2025Top Custom Mobile App Development Companies In New

Mar 13, 2025The Best Wardrobe Mica Designs to Elevate Your

Mar 13, 2025What are the most important tips for choosing

Mar 13, 2025Low-Cost Soil Thermometer – Buy from Certified MTP

Mar 13, 2025Ultimate Guide To Camping Gear Rental For Your

Mar 13, 2025How Do Kids Swings Benefit Physical And Mental

Mar 13, 2025What are the common applications and benefits of

Mar 13, 2025Nixware is a prominent name in the gaming

Mar 12, 2025Memesense: The Power of Memes in Shaping Culture

Mar 12, 2025Web Scraping For Big Data: Best Ways To

Mar 12, 20257 secret tips for choosing the best chiropractor

Mar 12, 2025র দিয়ে মেয়েদের ইসলামিক নাম: অর্থ ও মাহাত্ম্য

Mar 12, 2025How Glamping Can Help Unwind and Reconnect

Mar 12, 2025Understanding the Working of the IGBT Module

Mar 12, 2025Study Quran Effortlessly – Best Platforms and Tips

Mar 12, 2025The Ultimate Guide to Fence Installation

Mar 12, 2025Corteiz ® | CRTZRTW Official Website || Sale

Mar 12, 2025Al Hudaiba Dubai – A Complete Guide to

Mar 12, 2025How Does An SEO Company In Ahmedabad Enhance

Mar 12, 2025Order Reliable Tamper Tools at Certified MTP –

Mar 12, 2025Your style, Our Passion – Asaali Hoodie, Made

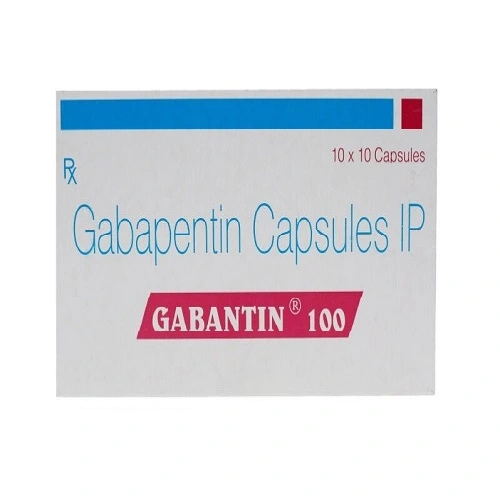

Mar 12, 2025Everything You Should Know About Gabantin 100 mg

Mar 12, 2025Where Can One Find a Trustworthy Supplier of

Mar 12, 2025Importance of the best trade show exhibit booths

Mar 12, 2025The Rise of Political Podcasts: Stay Informed and

Mar 12, 2025Where Luxury and Modernity Converge Stussy Fashion

Mar 12, 202511 Factors That Drive Up Swimming Pool Installation

Mar 12, 2025How Do Visa Assistance Service Providers Help You

Mar 12, 2025Hellstar Shirt The Ultimate Statement

Mar 12, 2025Top PhD Thesis Writing Services in India –

Mar 12, 2025Low-Cost Concrete Chute for Any Project – Shop

Mar 12, 2025A Beginner’s Guide to Investing in Liquid Mutual

Mar 12, 2025Importance of PR Agency in Healthcare Sector

Mar 12, 2025What are the best possible investment options in

Mar 12, 2025Elevate Your Home with Nibav Home Elevators

Mar 12, 2025Best Destination Wedding Spots in Allahabad for 2025

Mar 12, 2025What is Daman Online Game and how does

Mar 12, 2025How to Keep Your E-Bikes Running Smoothly with

Mar 12, 2025The Thrill of Axe Throwing: A Modern Adventure

Mar 12, 2025Get Expert Excel Assignment Help – Fast &

Mar 11, 2025The Ultimate Guide to Broken Planet T-Shirts: Style

Mar 11, 2025The Ultimate Guide to GV Gallery Pants

Mar 11, 2025“Essentials Hoodie | Fear Of God Essential Australia

Mar 11, 2025Boost Your Freelance Business with a Scalable Fiverr

Mar 11, 2025Why Rotary Lobe Pumps Are Preferred for Viscous

Mar 11, 2025What Are The Top Benefits of Using Indian

Mar 11, 2025What is the On Board Weighing System Price

Mar 11, 2025How to Hire an Illustrator for Corporate Branding

Mar 11, 2025Why is Sourcing Certification Important in 2025?

Mar 11, 2025Damaged Cars for Sale NJ: Your Guide to

Mar 11, 2025How to Choose the Best Boba Toppings for

Mar 11, 2025What are the most important tips that you

Mar 11, 2025How to Choose the Best Dubai Lights Manufacturers

Mar 11, 2025What to Consider When Selecting an Aircraft Charter

Mar 11, 2025Wrecked Car Auction Tips: How to Get the

Mar 11, 2025Car Fame: Your Destination for New Car For

Mar 11, 2025What Are the Most Effective Squirrel Removal Methods

Mar 11, 2025The Best Dove Hunting Gear for Women: A

Mar 11, 2025Top Surgical Instruments Shop in Lahore

Mar 11, 2025Top Google Ads Agency : Unlocking Success with

Mar 11, 2025A Comprehensive Guide to Lighting Installation

Mar 11, 2025Top Digital Marketing Agency in UAE for Business

Mar 11, 2025Air Ticketing Course in Rawalpindi Islamabad

Mar 11, 2025Al Karama: Exploring the Vibrant Heart of Dubai

Mar 11, 2025“Essentials Hoodie | Fear Of God Essential Australia

Mar 11, 2025A Comfortable Moving Journey from Delhi to Bangalore

Mar 11, 2025What Are 3PL Companies in Canada? A Beginner’s

Mar 11, 2025How to Build a Firearm Emergency Kit for

Mar 11, 2025Fall Fashion: Essentials Hoodie Layering Guide

Mar 11, 2025Civil Lab Technician Course In Rawalpindi-Islamabad

Mar 11, 2025Everything You Need To Know About Cement Bulker

Mar 11, 2025Exploring the Hype Behind the Felpa Stone Island

Mar 11, 2025What Are the Key Benefits of Using Local

Mar 11, 2025Best Rooftop Solar Panels in India | Rooftop

Mar 11, 2025How Python Became The Go-To Language for Programmers

Mar 11, 2025The Ultimate Guide to the Hellstar Hoodie

Mar 11, 2025Why Every Fashion Lover Needs a BAPE Hoodie

Mar 11, 2025Help by Virtual Medical Administrative Assistant

Mar 11, 2025Hellstar The Rising Star of Streetwear

Mar 10, 2025Best SEO Packages in India – DigitalGrow4u

Mar 10, 2025Why ISO 27001 Certification Is Crucial for Your

Mar 10, 2025Back Pain Management Guide: 7 Natural Tips for

Mar 10, 2025The History Behind Dsquared2’s Streetwear Staple

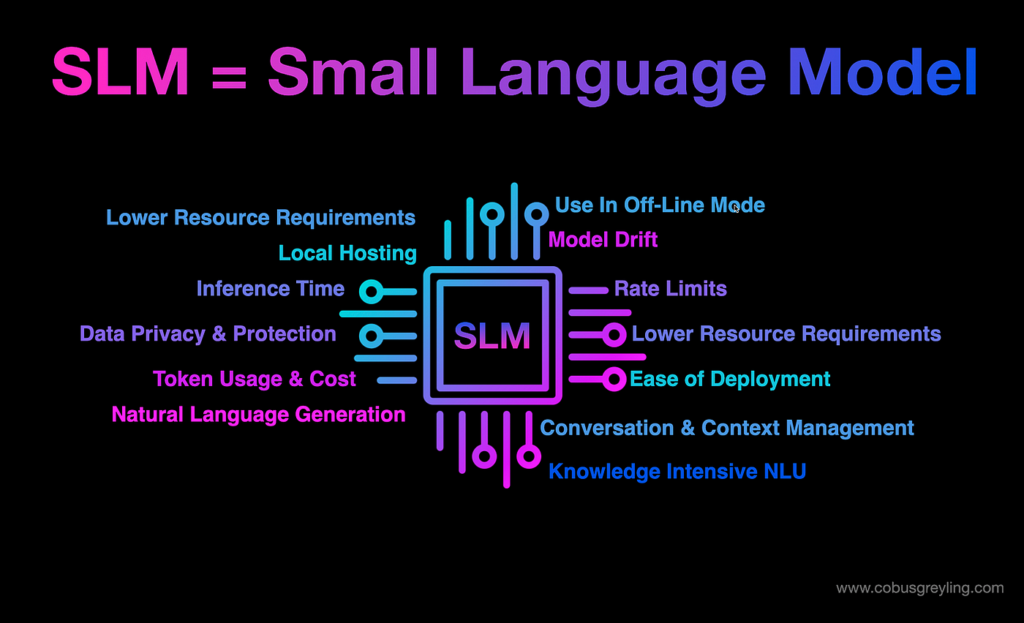

Mar 10, 2025Small Language Models: The Future of Efficient and

Mar 10, 2025What Tools and Platforms Are Covered in a

Mar 10, 2025What is nail art and courses to become

Mar 10, 20255 Proven to Reduce Claim Rejections and Improve

Mar 10, 2025Which is the best IELTS coaching center in

Mar 10, 2025What are the types of flex printing?

Mar 10, 2025Steps to Become an Educator with a Diploma

Mar 10, 2025How Legal Professionals Are Using AI Checker to

Mar 10, 2025Top-Rated CCNA Courses for Networking Professionals

Mar 10, 2025Hire Smart Contract Developers

Mar 10, 2025Discovering The Best Cab Service in London

Mar 10, 2025Enhance Your Bathroom with Stylish Accessories

Mar 10, 2025How to Choose the Best Block Paving for

Mar 10, 2025Apple iPhone 17 Pro Max Design: New Leak

Mar 10, 2025The Future of Employee Experience: Trends to Watch

Mar 10, 2025The Ultimate Guide to Playboi Carti Concert Tees

Mar 10, 2025The Untold Story of Khalistan Shaheed and Their

Mar 10, 2025How Wooden Sash Window Decoration Boosts Kerb Appeal

Mar 10, 2025Your Ultimate Guide to Equipping Your Home with

Mar 10, 2025Butter vs. Ghee vs. Oil: Which One is

Mar 10, 2025A Guide to Choosing an Affordable Aged Care

Mar 10, 2025Differences Between Square Tubing And Other Types Of

Mar 10, 2025The Top 2 Lash Services in Texas: Elevate

Mar 10, 2025Car Rentals in Brisbane: A Comprehensive Review of

Mar 09, 2025How to Increase Internet Speed

Mar 09, 2025Black Essentials Hoodie The Ultimate Blend

Mar 09, 2025Leading Audit Firms in Dubai for Business Compliance

Mar 09, 2025Corteiz Tracksuit The Ultimate Blend of Style

Mar 09, 2025Maui Kayak Tours in 2025: What’s New and

Mar 09, 2025The Ultimate Guide to Spider Hoodie: The Trend

Mar 09, 2025The Ultimate Guide to King-Size Bed Dimensions

Mar 08, 2025RideX Ltd – Reliable and Luxurious Private Hire

Mar 08, 2025Nasha Mukti Kendra /Diya Welfare

Mar 08, 2025Bosch | Power, Precision, and Performance for Every

Mar 08, 2025Why You Should Tailor Your CV for Every

Mar 08, 2025The 10 Most Beautiful Places to Visit in

Mar 08, 2025Reasons to Choose the Best Carpet Repair Services

Mar 08, 2025What Qualifies as a Truly Luxurious Villa

Mar 08, 2025Sleek and Smart: Modern Standard Lamps and Motion

Mar 08, 2025The Best Dishes to Try When Ordering Food

Mar 07, 2025Why It’s Important to Have Friends Outside of

Mar 07, 2025The Importance of VAT Return Filing Services in

Mar 07, 2025Essential VAT Tax Services Every Business Needs to

Mar 07, 2025Why Quality Ankle Socks Make All the Difference

Mar 07, 2025Mistakes to Avoid When Choosing the Best Hydrogel

Mar 07, 2025Explore ICAD Abu Dhabi – The Future of

Mar 07, 2025Why Al Nasr Plaza Residence is the Ideal

Mar 07, 2025Enhancing Security for Business and Compliance

Mar 07, 2025The luxurious jewelry brands of Pakistan: Where to

Mar 07, 2025Power of Custom Development Services

Mar 07, 2025Your Trusted Source for Genuine Products in Dubai

Mar 07, 2025Why V Boards Are a Must-Have for Roadside

Mar 07, 2025What Makes Shan-A-Punjab a Must-Try in Boston

Mar 07, 2025Top Study Abroad Advisor in Dubai for Seamless

Mar 07, 2025How Online Nursing Tutors Can Help You in

Mar 07, 2025How LED Strip Lighting Can Transform Your Home:

Mar 07, 2025Where Can I Find the Best Deals on

Mar 07, 202510 Reasons Why Hiring Direct Tax Consultants is

Mar 07, 2025Comfort And Convenience: The Key To Ideal Living

Mar 07, 2025Can you help me choose a research topic

Mar 07, 2025A Guide to Choosing the Right ORM Services

Mar 07, 2025How to Style Your Golf Outfit with a

Mar 07, 2025Enhance Your Space with a Durable Cable Railing

Mar 07, 2025Fast Water Softener System Repair You Can Trust

Mar 07, 2025Steps to Successfully Trade in Your Old Device

Mar 06, 2025Elementor #13497

Mar 06, 2025The Ultimate Guide to Choosing the Right PPC

Mar 06, 2025Where to get the best diamond rings for

Mar 06, 2025Exploring the Ethical Challenges of Generative AI

Mar 06, 20257 Important tips that you need to know

Mar 06, 2025Where to Find the Best Diagnostic Labs Near

Mar 06, 2025How Can a Group Online Chess Course Help

Mar 06, 202513 Hong Kong Tips Every First-Time Traveler Should

Mar 06, 202510 Things to Consider When Choosing an Online

Mar 06, 2025Leading Web Development Companies Nearby

Mar 06, 2025Quantum AI Market Demand, Suppliers And Forecasts To

Mar 06, 2025The Role and Importance of an Electrical Contractor

Mar 06, 2025Uses of Felted Wool in B2B Markets: A

Mar 06, 2025Why Managed IT Services Are a Game-Changer for

Mar 06, 2025Crafting an Effective Literature Review: A How-To

Mar 06, 2025Keep Your Skin Rejuvenate with Hydrafacial in Los

Mar 06, 2025Benefits of Hiring a Full Stack Developer

Mar 06, 2025How a Liverpool SEO Agency Can Boost Your

Mar 06, 2025Tips to Choose the Best BMW Service Nearby

Mar 06, 2025Hire a Law Assignment Writer for Top-Notch Law

Mar 06, 2025Why Al Muwaileh Sharjah is a Great Place

Mar 06, 2025After-School Programs for Special Needs: A Guide for

Mar 06, 2025Top Hair Extensions Ontario & Wigs for Hair

Mar 06, 2025Why Homeowners Love French Doors for Elegance

Mar 06, 2025Best Cricket Gears Shops Near Me & Online

Mar 06, 20255 Tips for Health Policy Comparison

Mar 06, 2025Wooden Furniture Online – A Timeless Elegance for

Mar 06, 2025What Are the Benefits of Offices for Rent

Mar 06, 2025What Is a Windows Dedicated Server?

Mar 06, 2025Best Rhinoplasty & Liposuction Surgeons in Mumbai

Mar 06, 2025Reasons to Buy Refurbished Water Well Drilling Rigs

Mar 06, 2025Discover the Oppo A3 Price in Pakistan for

Mar 06, 2025Leading Door and Window Manufacturers – A Detailed

Mar 06, 2025Common Roofing Problems in Florida and How to

Mar 06, 2025Do My Coursework: The Ultimate Guide to Getting

Mar 06, 2025What is Google Workspace’s Business Standard Plan?

Mar 06, 2025Stussy Hoodie: The Ultimate Guide to Style, Care

Mar 06, 2025Al Khawaneej Dubai – A Blend of Tradition

Mar 06, 2025Can a tax accountant in Preston understand my

Mar 06, 2025How can you grab the best deal while

Mar 06, 2025Microsoft Dynamics 365 Partners in UAE: Benefits &

Mar 06, 2025Affordable CT Scan Price in Bangalore – Procedure

Mar 06, 2025EEG Test in Bangalore | Procedure, Cost, and

Mar 06, 2025Convenient & Safe Blood Sample Collection from Home

Mar 06, 2025What is the Time of Pagoda Visit?

Mar 06, 2025Why Car Paint Repair Is Essential In Dubai’s

Mar 06, 2025Best Cleaning Products for Deep Cleaning Your Home

Mar 05, 2025DAFZA Approved Auditors: Ensuring Compliance

Mar 05, 2025Top Digital Marketing Agencies in India and Dubai

Mar 05, 2025Best Cafr in Deira City Center: A Coffee

Mar 05, 2025Top Hair Coloring Techniques Every Color Hair Salon

Mar 05, 2025Custom Software Development Services

Mar 05, 2025Finding Justice: Why You Need a Phoenix Truck